The Museum as Ethics Classroom

On February 9, 2017, a few weeks after Trump’s presidential inauguration and the Women’s March on Washington, the Brooklyn Museum held a historic gathering, entitled “Defending Immigrant Rights: A Brooklyn Call to Action.” The auditorium was packed to capacity and the energy in the room was palpable. Panel speakers included the Palestinian-American Women’s March organizer, Linda Sarsour, who was then also the executive director of the Arab American Association of New York; Murad Awawdeh, from the New York Immigration Coalition; Carl Lipscombe, from the Black Alliance for Just Immigration; Lisa Schreibersdorf, from Brooklyn Defenders Services; and Nayim Islam, a youth organizer from DRUM/Desis Rising Up and Moving. The speakers were phenomenal and shared collective strategies being developed in response to Trump’s policies.

At the end of the gathering the space was opened up for questions. As Director of Education at the Brooklyn Museum, I was curious about how they understood the role of art in the emerging struggles for social justice. Their responses varied; one panelist mentioned being blown away by the range of artistic expression manifested in the signs created for the Women’s March, others commented on the healing, stress-relieving benefits of art-making, another mentioned using art as a carrot-stick, in other words, as an incentive to get people through the door. While their responses were sensible, I couldn’t help feeling like they missed the point of my question, and I was left trying to pin-point what it was that I felt they had missed.

What is the relationship (if any) between art and social justice? This is a particularly poignant question for art educators working in encyclopedic museums, such as the Brooklyn Museum, that hold a historic connection to colonialism, imperialism, and scientific racism. However, museums can also serve as public forums that allow for a different kind of public engagement—one that makes space not just for our rational selves but also for our emotional, sub-conscious selves which, I would argue, is part of the power of art. Spaces that allow for this kind of interaction are rare. One thing that this last presidential election has made clear is that we have lost our ability (assuming we ever had it) to engage in real dialogue, which requires not just voicing ideas, but also listening and reflecting in an open, honest, and compassionate way. The other thing this last election made clear is that information and facts are not essential for change–but feelings and perceptions are paramount.

In 1896, Booker T. Washington delivered an address at the Brooklyn Museum (then the Brooklyn Institute of Arts & Sciences) that included this statement: “The study of art that does not result in making the strong less willing to oppress the weak means little.” It strikes me that he is recognizing “the study of art,” what today we call “arts education,” as potentially transformative. The implication is that interaction with and exploration of art can shift social sentiment by engaging our belief systems, yearnings and desires.

B.T. Washington’s ideas on what we now refer to as social justice were no doubt informed and inspired by Frederick Douglass; whose biography he wrote and published in 1899. In his 1857 “West India Emancipation” speech, Douglass declared, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” In Douglass’ view, the struggle “may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle.”

So Washington, in his statement, is also inferring that in order for the study of art to make the strong less willing to oppress the weak, it must involve struggle. For arts educators, the context for this struggle is often in the realm of uncomfortable conversations that can arise when we facilitate open-ended conversations with a piece of art. Rather than shying away from these difficult or tense encounters, we should push ourselves and the audiences with whom we engage, to investigate the contours of our discomfort, always remembering to do so with empathy. Uncomfortable conversations hold great transformational potential—this is where we strike gold!

Intersectionality

Fast-forward 60 years. Second-wave feminists begin drawing attention to the ways in which “the personal is political.” Then, in the 1970s and ‘80s Black and lesbian women scholars and artists bring to light the need for an “intersectional” approach to dismantling institutions of oppression. Audre Lorde sheds light to the simple truth that, “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” We no longer define “the strong” in relationship to “the weak” only in terms of race and class, but must also consider gender, sexuality and multiple other configurations of social identities. We can no longer speak in generalities about “the weak” as if the life experiences of all marginalized and oppressed people were interchangeable.

While poor, “Black rural workers” or “white proletarian men working in factories” may, indeed, represent real categories for people impacted by structural oppression, each individual within these categories holds multiple, infinitely more complex identities: being gay, trans, light-skinned, heavy-weight, disabled, a poet, etc., and each configuration is political in myriad ways. Furthermore, as traditional notions of “the weak” and “the strong” expand and are problematized, we are also faced with the reality of being able to hold in one physical body experiences of both privilege (where we benefit from the oppression of others consciously or unconsciously), while at the same time, in other social contexts, experiencing oppression ourselves. I may be a woman of color raised by a working-class single mother, but I am also a light skinned, ivy-league graduate with a U.S. passport. On the other hand, these experiences are not equally distributed amongst all. Our particular social location still makes it so that some of us bear the brunt of more experiences of structural oppression while others tend to bear more of its benefits. So, for example, while I hold a tremendous amount of privilege, I’m certain that John D. Rockefeller held more. The point is that the very notion of “social justice” becomes an active endeavor that requires constant vigilance, critical reflection of the world around us, balanced with self-reflection, and humility.

One of the books that most impacted my thinking around these ideas is Paulo Freire’s groundbreaking Pedagogy of the Oppressed. The first time I read it, I was both inspired and irritated by his approach; inspired because Friere problematizes the idea of what it means to be a revolutionary, and irritated because his language continuously betrays a monolithic (and patriarchal) understanding of “the oppressed.” Nonetheless, this is the book that made me believe and long for revolution, in part because it is infused with an almost spiritual understanding of the liberatory potential of educational experiences. While Freire is essentially a Marxist, he not only questions the hegemony of capitalist oppression, but he is equally critical of leaders of “radical” social justice movements who feel they must indoctrinate the masses with the “correct” ideology that will liberate them. Rather, for Freire, the true educator is primarily driven by faith in students’ ability to critically see and interpret the world, which will necessarily lead them to liberation:

“The insistence that the oppressed engage in reflection on their concrete situation is not a call to armchair revolution. On the contrary, reflection–true reflection–leads to action. On the other hand, when the situation calls for action, that action will constitute an authentic praxis only if its consequences become the object of critical reflection…Otherwise, action is pure activism. To achieve this praxis, however, it is necessary to trust in the oppressed and in their ability to reason. Whoever lacks this trust will fail to initiate (or will abandon) dialogue…”

Art as Imagination

So what does it mean to develop a social justice arts education practice? Fundamentally, it means to acknowledge the reality of systemic oppression and power imbalance while allowing for the emergence of new perspectives and understandings. Robin Kelley describes this as the “radical imagination”; the ability to move beyond critiquing and tearing down oppressive structures, to actually imagining what we want things to be like:

“…we must tap the well of our own collective imaginations…do what earlier generations have done: dream. Trying to envision ‘somewhere in advance of nowhere,’ as poet Jayne Cortez puts it, is an extremely difficult task, yet it is a matter of great urgency. Without new visions, we don’t know what to build, only what to knock down.”

Extremely difficult task, indeed! In part because we are inundated with models and systems that betray a deep lack of imagination: a political system that does not truly represent or engage people; a TV and film industry that repeatedly cranks out the same tired models of heteronormative romance; an economic system based on exploitation and competition; a criminal justice system founded on racism, fear and violence; representations of sex and sexuality that can’t seem to come up with anything other than pornography. The list goes on and on. These models pervade our culture because we don’t spend enough time playing, experimenting, and imagining how things might be otherwise. This is why we must look at those realms in our collective consciousness that privilege the imagination and the human capacity to create. Continuous engagement with artistic practices strengthens our imagination muscle. Arts education is essential, because it builds our ability to dream and imagine beyond our present condition.

How do we understand the idea of art?

ärt/

the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination

Etymology: early 13c., “skill as a result of learning or practice,” from Old French art (10c.), from Latin artem (nominative ars) “work of art; practical skill; a business, craft,” from PIE *ar-ti- (source also of Sanskrit rtih “manner, mode;” Greek arti “just,” artios “complete, suitable,” artizein “to prepare;” Latin artus “joint;” Armenian arnam “make;” German art “manner, mode”), from root *ar- “fit together, join” (see arm (n.1)), which makes art etymologically akin to Latin arma “weapons.”

What strikes me about the root of the word is how active it is. The words used to describe its core meaning are much more about a way of doing than about a thing you hang on the wall. Activist, art-educator, and nun Corita Kent describes “art” in the following way:

“To create means to relate. The root meaning of the word ART is to FIT TOGETHER and we all do this every day. Not all of us are painters but we are all artists. Each time we fit together we are creating—whether it is to make a loaf of bread, a child, a day.”

Art as Dialogue

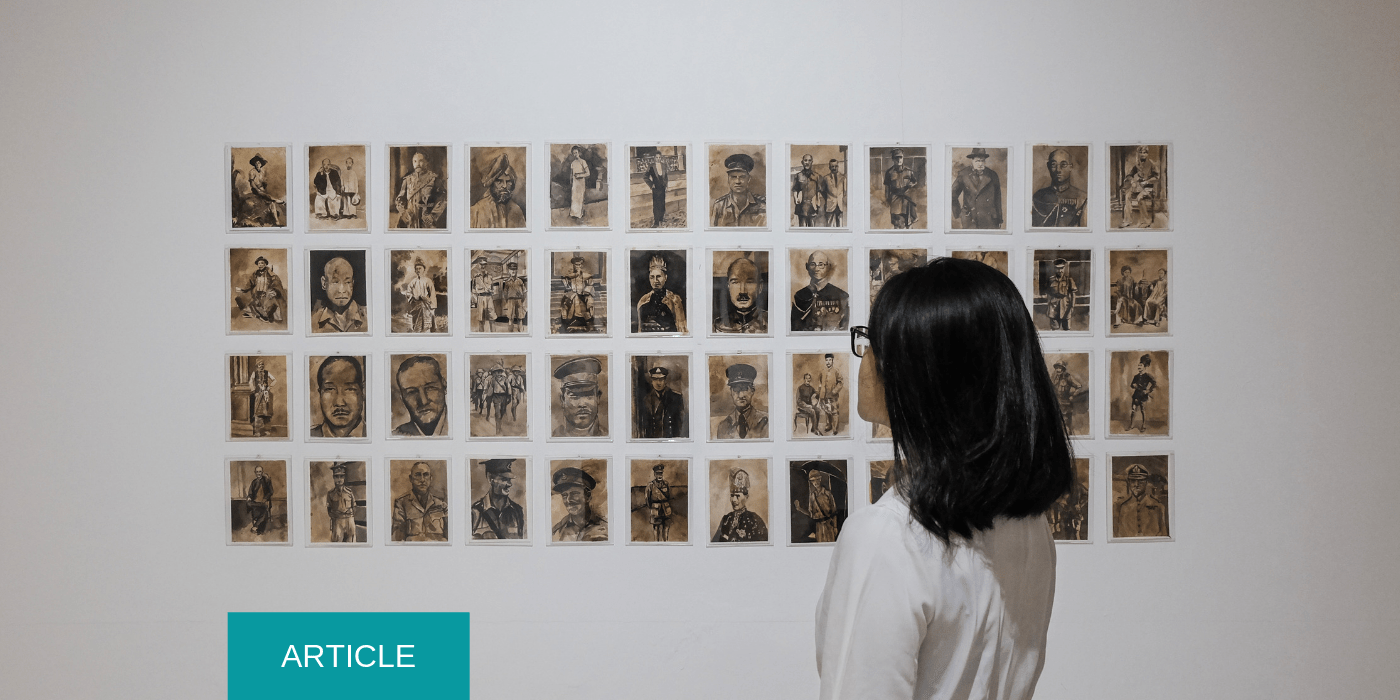

At the Brooklyn Museum I’ve had the privilege of working with art education professionals committed to the dialogical process ignited by the power of art. Part of our practice as educators is about continually reflecting on our practice to understand the ways in which we are or are not effective in creating educational experiences that reflect the beautiful struggle that a true social justice practice demands. Much of what we do is to create opportunities for dialogues grounded in multi-sensory experiences with artworks. We do not attempt to deliver information-packed or curatorial talks to visitors (although these also have value). Rather, we ask audiences to interact with a piece and share what they see, what they feel, and we make them accountable for their interpretations by continually asking them “What do you see that makes you say that?” We encourage self-reflection and the articulation of different perspectives. We introduce key pieces of information on the art or artist to add complexity and push the conversation deeper, but ultimately we recognize that the more opportunities diverse groups are given to look, listen, express, and wrestle with meaning, the stronger their ability (and our ability) to develop into ethical human beings, able to imagine a more humane society.

The Centrality of Art

Both art and social justice are better understood as verbs than as nouns. The essential power of both is unlocked by understanding them as processes. Yes, social justice is about low-income housing, desegregation of schools, tackling the criminal in-justice system, and defending immigrant rights. But it is only about these things because people have collectively reflected on lived experiences around these issues, and dialogued, and re-visited past assumptions, and come to realizations, and struggled to express ignored truths, and heard the truths of others, and from this process a vision emerges of what is needed. The concept of art can also, at its core, be understood as a process/approach towards learning and doing. Why are such disparate activities such as singing, painting, a poem, a movement, certain photographs, all grouped under the term “art”? I would argue that it is because they are all expressions that bridge our inner terrain to the outer world. And in this way, we are pushed to know ourselves, each other, and the world around us from perspectives that challenge us to see beyond ‘what is there.’ There is an intimate relationship between all authentic learning and Art. Within this context, a social justice perspective also requires us to expand and question traditional notions of “Fine Arts” and artistic “Canons”.

While my understanding of power, oppression, and revolution continues to expand and to gain greater and greater complexity, I find myself continually returning to Freire, even more than 20 years after I first encountered his writings. While some aspects of his ideas feel dated, there is still an intrinsic truth that he expresses that still resonates deeply with what I know to be true. “The object in presenting these considerations,” he states at the end of his opening chapter, “is to defend the eminently pedagogical” and here I would add–ARTISTIC, “character of the revolution.”

Art is not an addendum, a distraction, a pleasant byproduct, or even a tool to be used in service of the “real” work of political struggle for social justice. Art and art education are essential to social justice because social justice requires social imagination. Art is not a Renoir painting, just as social justice is not a march. Rather, both art and social justice are essentially pedagogical endeavors in that they hold the potential, through dialogue and the activation of personal and collective imagination, to transform our very beings and to transform the oppressive realities that engulf us. The combination of these elements–whether in an art museum, a community center, a classroom, or the streets–holds the potential to change the world.

Adjoa Jones de Almeida is the Director of Education at the Brooklyn Museum and is committed to utilizing arts education as a vehicle for personal and collective transformation. She earned her Master’s from Columbia University/Teacher’s College in International Education Development and was a teacher, community organizer and arts educator prior to joining the Brooklyn Museum. She is a 2017 92Y/Women in Power Catherine Hannah Behrend Fellow in Visual Arts Management.