Throughout my two decades teaching, ethics has been central to what I view as my dual role of educator and mentor. Ethics, from the Greek “ethos,” meaning “character,” comprise the principles and priorities that govern people’s actions and their relationships with others. What follows is an account of an effort to create on a small scale an ethical learning environment based on inclusivity and equity rather than individual competition and test scores.

My name is Carlo Vidrini. I teach high school robotics. An immigrant from Trieste, I arrived during the summer of 1997 and began teaching the following year. Since the New York State Education Department didn’t accept my European teaching credentials, I worked during the day to support my family and took classes at night. 2004 was a momentous year for me; I was honored with both American citizenship and New York State permanent teacher certification.

Our town of Peekskill, 40 miles north of New York City, although economically deprived, is rich in culture and community spirit. A majority of families are Hispanic immigrants, largely from Guatemala and Ecuador, and African-Americans; parents are committed to ensuring their children have opportunities they didn’t have.

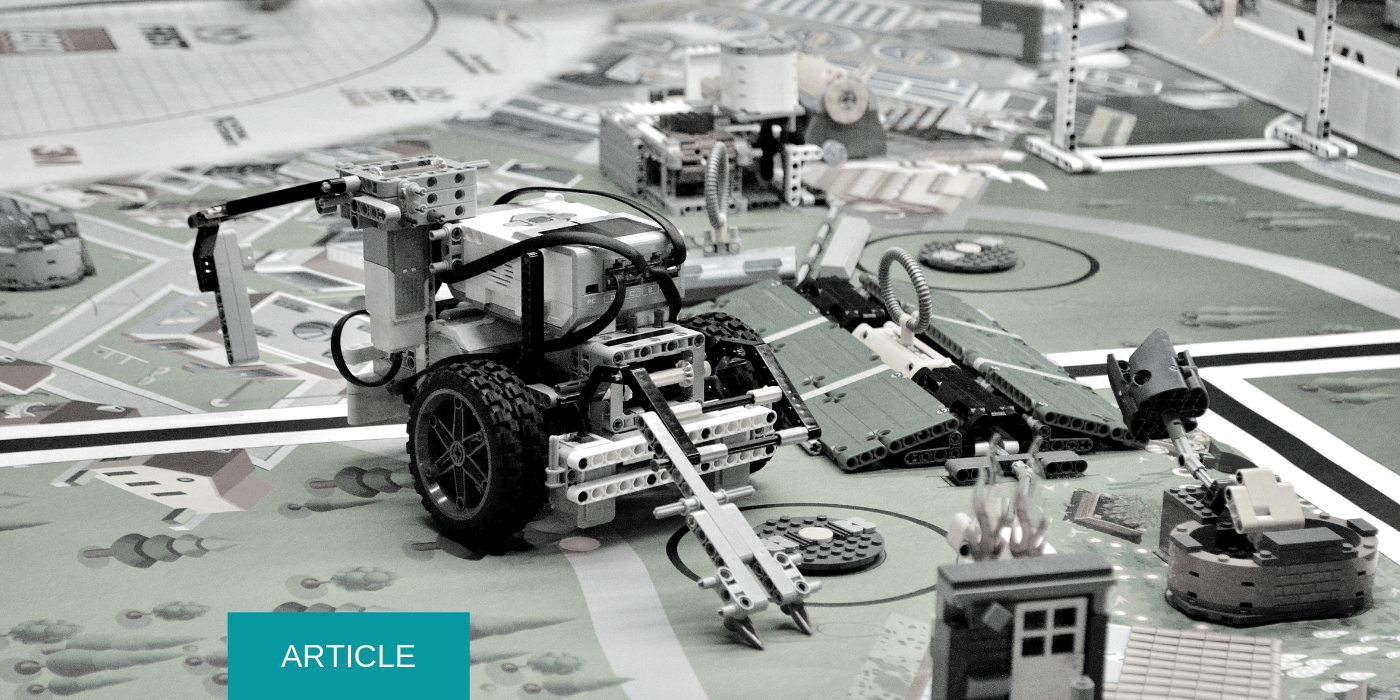

We started our robotics program in 2013 as a middle school elective. The following year, we added high school classes. The excitement was palpable; building robots was creative, challenging, and collaborative. Knowing our community’s and our students’ needs, I saw an opportunity to expand from a cluster of classes into a vibrant, multi-dimensional program. The robotics community we created was unlike any the students had experienced, and increasing numbers of youngsters wanted to be part of it.

Today, we have two high school robotics teams, both of which participate in regional and state competitions. Victories in the FIRST Tech Challenges (FTC) and Rube Goldberg competitions have resulted in invitations to National and World Challenges! The trophies have generated so much buzz around school that a new club has been created.

The PTO (Parent Teacher Organization) and SEPTO (Special Education Parent Teacher Organization) want to be part of it. Civic organizations, including the local NAACP and Rotary chapters, are eager to support the program. Most importantly, student enthusiasm and dedication are off-the-charts.

Inequities

Drawing on the thought of the 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, I have always considered it my responsibility as an educator, not only to provide my students with information but also to help prepare them to be ethical, engaged citizens. But in a society that normalizes ruthless competition and conspicuous consumption, it has often been an uphill climb.

Let’s start with the infamous “No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB).” The initiative’s best part, its title, was a gross misrepresentation of its effect. NCLB called for increased testing and standardization, leaving those students in need of individualized support and services further behind than ever. The focus on test prep exacerbated the learning gaps between children of privilege and other students. There was no room for independent thought or experimentation, learning for the joy of it. The structure of rewards and penalties resulted in unethical behaviors on the part of some schools and districts.

Critical Thinking

Despite federal pressure to standardize and test, in our robotics program, we have been able to create a positive learning environment, one which values the learning process — independent thinking, creativity, and risk-taking — over test results. All students have the opportunity to take STEM and STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math) classes. They develop habits of critical thought, experimentation, and investigation that guide their future endeavors. The program encourages trial and error learning; it recognizes that failure is a normal part of students’ experimentation and works to build upon it. This has only been possible because I have the support of school administrators and the local community.

Collaboration

Europe and the USA seem to have very different approaches to subject mastery. Europeans value general knowledge more whereas Americans are encouraged to specialize. Here’s an example from basketball: A Slovenian playmaker is also capable of playing guard and point guard positions. An American player, on the other hand, learns only one position. He may be superior to the European in that position, but may be less valuable to the team overall since his skills are so specialized. European training emphasizes the team whereas the American approach focuses on individual excellence.

I’ve long been a proponent of Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs theory, developed between 1943-1954. Recently, I came across an article in Psychology Today by Dr. Pamela B. Rutledge. “None of these needs — starting with basic survival on up — are possible without social connection and collaboration…,” Dr. Rutledge observes. “Needs are, like most other things in nature, an interactive, dynamic system, but they are anchored in our ability to make social connections.” Based on my classroom experience, I believe she is correct. Healthy relationships with peers and mentors are key to academic and personal success; community is a basic need. Social connection is not a separate level of need, but rather an integral component of need fulfilment at every level.

Impact

The inclusive, collaborative experience of building robots is empowering to students who have little control over many areas of their lives. As well, it gives them a chance to apply their theoretical knowledge of math and physics to concrete, functional, and unique machines. The students keep engineering notebooks, detailed daily work logs, which memorialize what they have accomplished over time and as a team. Their robots are their robots.

The enthusiasm for the program (students arrive at school at 8 am over summer vacation to work on their robots!), the pride in their work, and the respect they develop for their team members has been extraordinary. I think it provides a model both for other STEM/STEAM activities and for the students as they move on to higher education and work environments.

Following a 25-year career in electronics, Carlo Vidrini has taught robotics, pre-engineering, and drone technology in Northern Westchester, and has been a Mentor in the USFIRST FTC Robotics Competitions since 2009.

This video gives us the opportunity to see a little bit of Carlo’s work in building the robotics team now known as the “Iron Devils”.