As practitioners and teachers of Emotionally Responsive Practice (ERP) at Bank Street College, we have the privilege and adventure of stepping into a wide range of settings in which grownups work with groups of children. We travel from daycare centers to independent schools, from charter schools to NYC public schools, seeing classroom practice with children ranging in ages from infants to 13 years old. Classroom management and having children learn to take responsibility for their own behavior are common challenges. In this article, we highlight what we see as negative and harmful trends in behavior management and introduce some core concepts and language of Emotionally Responsive Practice at Bank Street , an approach to working with children developed based on deep knowledge of child development and a respect for children’s life experience (Koplow, 2002, 2007, 2009). These anecdotes contextualize our discussion.

Stories from the Field: Part I

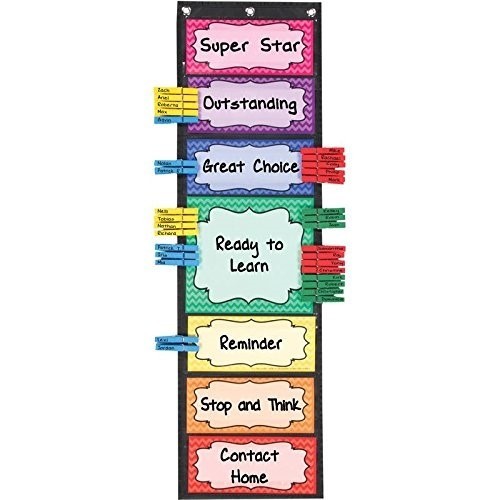

An ERP consultant sits with a first grade teacher in an “academically-focused” charter school, who tells the consultant of a child who is constantly “flipping out” in the classroom and whose tantrums often escalate so fast and intensely that he must leave the classroom several times a day. When the consultant says, “describe to me what happens when he flips out,” the teacher replies that one thing that always triggers him is when his clothespin is moved downwards on the behavior management chart, where different-colored cards indicate to children where their behavior falls in the realm of acceptability (see figure 1). When the consultant suggests that the behavior chart may not be the best way to deal with this child’s behavior, the teacher quickly replies that it wouldn’t be fair to the other children if this child didn’t use the same behavior chart.

A three year old boy is crying miserably upon waking up from his nap. His caregivers are busy helping other children with their blankets and cots as he sits on his cot unattended. “What’s happening?” asks the consultant in the room, pointing to the crying child. “ Oh. He does that every day when he wakes up,” says the teacher. She addresses the child. “Daniel, I told you before that big boys don’t cry. If you want to ride the big boy bicycle when we go to the yard, you’d better stop that crying!” At this, Daniel throws his shoe, unintentionally hitting another child passing by. The other child stands still in shock for a moment and then bursts into tears. The teacher shakes her head. “I told them to keep him with the two year olds, but they gave him to me anyway!” she tells the consultant in a loud voice, exasperated. Then, turning to Daniel, she says, “ There’ll be no bike riding for you today! You can sit and watch while the other children ride.”

As 8th grade students file into their classroom, their teacher instructs them to remove their outerwear and prepare for learning. One child tightens the strings of his hooded sweatshirt, hiding his face, and slumps down in his seat. When the teacher challenges him, he stands up, indignant, insisting that he will keep the sweatshirt on. The interaction ends with the frustrated teacher telling the student to leave the classroom and go see the dean. The dean writes up a report, adding to a growing file of this student’s negative behavior.

The Risks of Behavior Modification Systems: Shame and Punishment

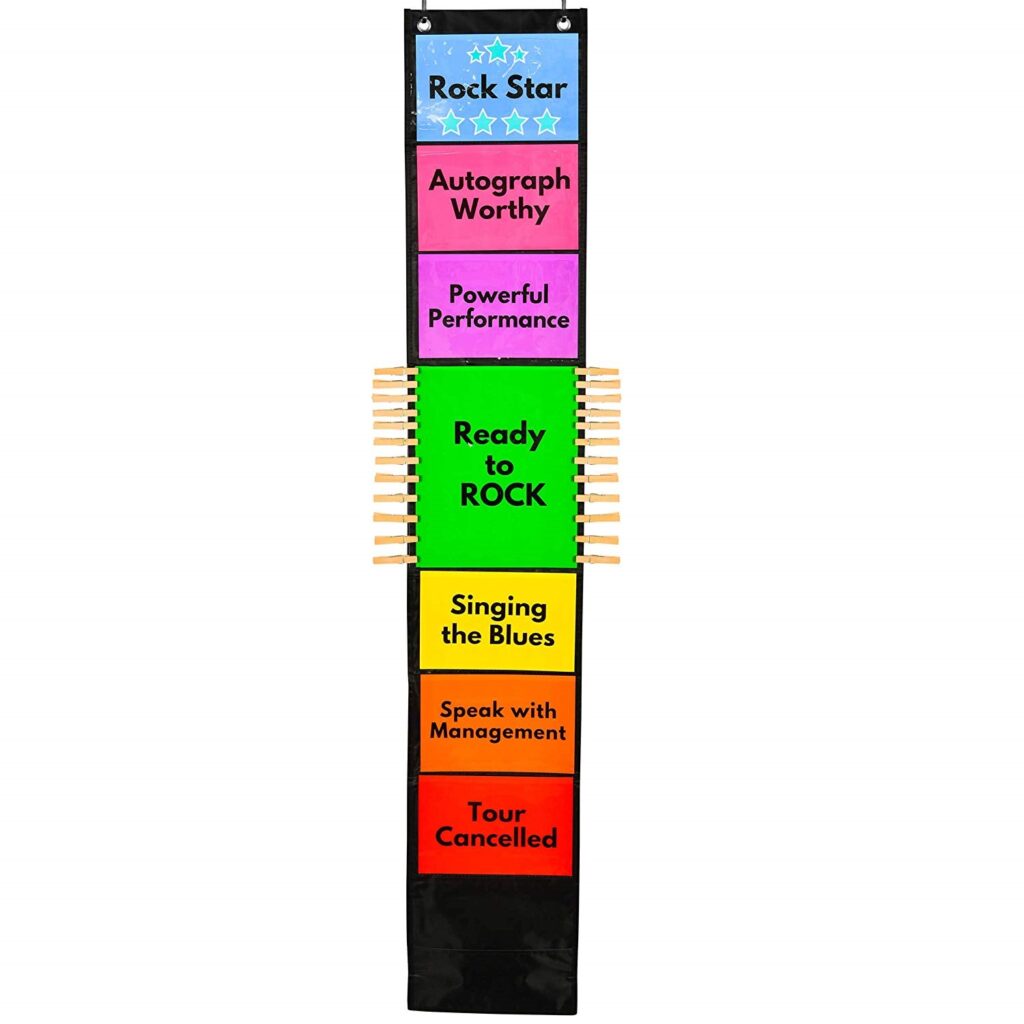

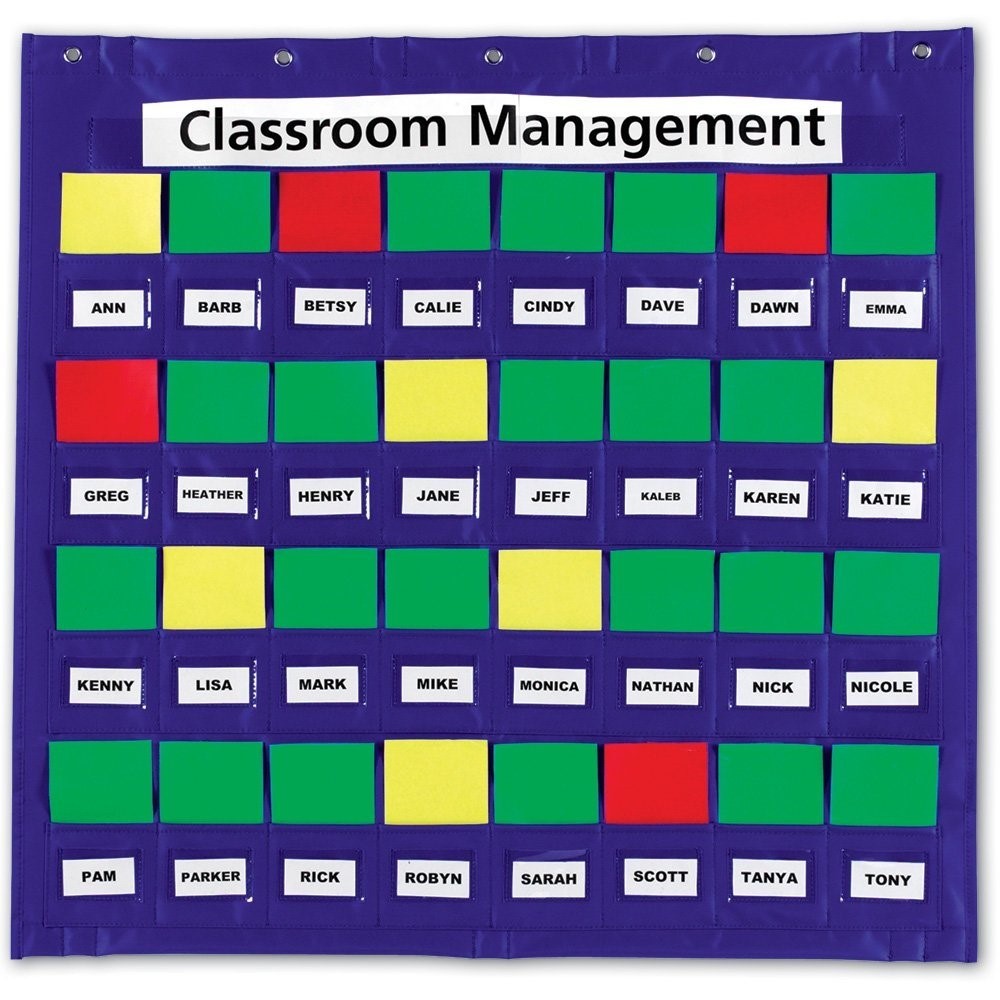

Educational programs for children often face the dilemma of how to manage challenging behaviors in increasingly stressed school environments. In most settings, due to external pressures, there is less and less time for authentic connection-making or creative or self-directed work, and more and more pressure on teachers and students to “perform” academically. More and more often, we see schools relying on implementing behavioral management programs to manage and shift children’s behavior. The basic premise of these programs is to reinforce positive behavior with a rewards system. In one of the examples above, we see the use of a behavioral modification chart. Typically, charts have levels or ranks, and the teacher moves each child’s name or number to a particular level based on the child’s most recent behavior.The highest card indicates that a child is meeting or exceeding the behavioral expectations in the classroom. The lowest card usually indicates that the teacher will call home, something that we frequently witness causing an undue amount of anxiety for children of all ages. In many classrooms that we visit, it seems to be the case that these behavior management systems are relied upon to encourage and demand compliance from children. It is not unusual for the children who struggle the most to adapt to classroom norms to also be the children most easily triggered by the downward movement of their clothespins or cards, which publicly demonstrates their negative value in the classroom.

Often schools carry this theory even further by applying consequences (read “punishment”) for low-ranking behavior, such as loss of recess or other special experiences, or a call home. Not surprisingly, the results of implementing these behavioral programs sharply highlight and replicate a macro-system based on shame instead of support, control instead of empowerment, punishment instead of healing: a system that invalidates young children’s deeply-felt experience of their own lives. It has been our observation over years of consulting that behavioral modification systems are implemented more often in schools in poor communities and communities of color and that, in racially diverse classrooms, they are used more regularly with children of color.

Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot writes: “In our efforts to control and measure, in fact, we often confuse difference with deviance, illness with identity; we pathologize, exclude, and then label those children who do not fit the norm–who trouble the waters, who misbehave–and we reward the teachers who contain and squelch the troublemakers” (in Shalaby, 2017, p.xi). Indeed, we see behavior modification systems as an effort on teachers’ parts to contain children while ignoring the emotions that underlie their behaviors. Carla Shalaby writes: “Teachers in training learn to punish transgressions because it is not controversial to be castigated if you misbehave. It is your choice and your fault. This logic is deeply embedded in the American psyche—the nation with one of the highest incarceration rates in the world—and it justifies our decision to throw away young lives by making young people think the fault for that exclusion is entirely their own” (Shalaby, 2017, p.xxii). It is easy to make the connection between punitive systems in school and the school-to-prison pipeline that has been widely and clearly documented in recent decades.

Let us return to Stories From the Field: Part 1. Our experience is that the vast majority of teachers and administrators want to support children, and that behavior modification systems such as the behavior chart are often introduced with the positively-framed goals of helping children to acquire self-management skills and creating a positive learning space. Unfortunately, these systems are far more likely to induce a feeling of shame in children who cannot meet the criteria on a given day, or every day. Brene Brown (2012, p.69) defines shame as, “the intensely painful feeling of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love and belonging.” When we see children vehemently deny that they did anything wrong, we understand that they would rather feel any other feeling than shame. While teachers often express frustration that children do not want to take responsibility for their actions, we prefer to interpret those children’s denial of wrongdoing as a natural, human reaction of avoiding shame, and ensuring self-protection. The rare children whom we have observed who are able to acknowledge that they hurt others and sincerely apologize are those who have been most well-supported emotionally in and out of school. We propose that teachers shift the lens through which they view the moment in which the child “refuses to take responsibility for his actions” to a lens of compassion, using their knowledge of development and respect for children’s life experiences. Utilizing a pathway through relationship and emotional literacy, teachers can empower students to accept responsibility without feeling shamed in the process. The following anecdotes exemplify what such a shift in teacher practice toward a lens of compassion might look like.

Stories from the Field: Part 2

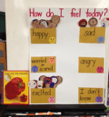

A class of four-year-olds has recently started using individual feelings charts in the classroom. One child is especially drawn to using his, and teachers have noticed that since he has had the ability to show his feelings on his own personal feelings chart, his outbursts have diminished. One day there is an unexpected fire drill, something that has caused him great agitation in the past. On this day, he runs to his feelings chart, moves the clothespin to “scared,” quickly finds a teacher’s hand to hold, and participates calmly in the fire drill. His teacher is able to talk to him later about how scary fire drills can be, and how glad she is that he could tell her his feelings using the chart.

An exhausted third grader puts his head down on the desk, having crumpled up his math assignment and thrown it on the floor. His teacher quietly acknowledges his fatigue and frustration, and invites him to rest in the cozy corner for a while. While he lies on the soft beanbag, in this small space, he holds his classroom teddy bear for comfort. Eventually, he reaches for his journal where he can write or draw something about what is making him feel so tired and frustrated. His teacher will read it if he wants her to.

In a similar anecdote to the 8th grade scenario above, instead of publicly challenging the student, the teacher approaches him quietly when all begin writing. He observes that when asked to remove outerwear, this student kept his on; he says, “It looks like you really don’t want to take your sweatshirt off today.” The student confides that the sweatshirt was a gift from his late grandfather and is helping him feel connected to his memory. With this knowledge, the teacher allows the student to keep the sweatshirt on for today, and makes a mental note to find time to further connect with the student and to let the guidance counselor know he may need some space to process. The teacher also makes a mental note to reconsider his own policy regarding outerwear, realizing that the clothing may provide a feeling of security and retreat for these older students who still experience strong emotions.

Emotional Literacy: Healing and Validating

In Stories From the Field: Part 2, teachers have internalized ERP concepts of “inviting and containing” and “relationship-based teaching.” Instead of behavior charts, they have created “feelings charts.” Instead of removing the children from their community, they have provided quiet areas for children to retreat from group life when their feelings become overwhelming. Feelings Charts, cozy corners, and other types of emotionally responsive invitations are alternatives to behavioral management programs. Feelings charts give children the opportunity to think about how they feel, and to communicate those feelings to the adults in the classroom. Many children struggle to make sense of their internal states, and feelings charts help children to develop emotional literacy.

Adults can help children use the charts to think about cause and effect. For example, “You came in this morning and you were feeling angry, and now you knocked down his block building. I wonder if you did that because you were feeling angry?” When children are able to identify feelings, they are more likely to develop self-regulation and to find more constructive ways to express them.

Using Feelings Charts: Introducing Emotional Literacy

In the current political era, the importance of the social emotional learning (SEL) that happens in school settings has begun to be more widely recognized. “Trauma-informed practice” has become a buzz-phrase, and more funds are being allocated to SEL. We recommend teaching emotional literacy through feelings charts. A feelings curriculum is one of the basic recommendations we make at all grade levels. We have come to view reflecting children’s experiences and supplying language to express their feelings as acts of radical love. Naming a child’s feelings humanizes the child for the teacher who is struggling to support that child. The behavior becomes secondary to the human value of the child experiencing the feelings at the root of the behavior.

We suggest teachers incorporate feelings charts in stages, first introducing them and making them part of their classes’ daily routines, soliciting children’s ideas and observations. After a while, children should be invited to use the charts independently. Children should be able to move their names (or popsicle sticks, or pictures, or magnets) on their own. This can happen as they come into the classroom in the morning. It should be stress-free. Teachers should invite children to move their indicators throughout the day as necessary. This helps teachers to track how children are feeling at school, and helps both children who struggle with articulating their feelings and children who act out their feelings to express them in a productive way. Some children may use the chart frequently at first and less so over time while others may continue to use it throughout the school year and some may need their teachers’ help to use it at all. As well, teachers can always draw the class’s attention back to the chart when they observe that the theme of feelings is relevant.

A teacher who recently implemented a feelings chart in his K-1 classroom comments, “The process of creating the feelings chart brought kids into touch with a greater range of feelings and helped expand their feelings vocabulary. We looked at characters in literature and named and identified with their feelings. Children illustrated the feelings, and used those illustrations as part of the feelings chart. This process, along with the introduction of our “peace nook,” has allowed the children fuller recognition of a variety of feelings, especially strong feelings, in themselves and in others.”

Little by little, as teachers realize the benefits of their initial efforts to incorporate more emotionally responsive approaches, we see them first shift their thinking, and then shift their practices further. By inviting children to share the authentic stories of their lives and naming and reflecting the feelings surrounding those stories, teachers and schools come to know children in deep and meaningful ways. The children in turn feel understood, valued, and safe. Instead of focusing on stopping behaviors, we encourage educators to invite schools to understand more about the complex web of reasons that children act out at school, and how to listen deeply to what they are communicating through their behavior. Research shows us the power of relationship and community in regulating toxic stress in the bodies of children and adults alike. (https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/wp1/) (developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/tackling-toxic-stress/pushing-toward-breakthroughs-using-innovative-practice-to-address-toxic-stress/) Classrooms and schools must become communities that courageously invite and hold the real struggles, successes and experiences of all children, so that these spaces can become grounds for healing and growth, not shame and punishment.

Figure 1: Examples of classic Behavior Modification Systems

Figure 2: Examples of Feelings Charts in the classrooms where we consult

References:

Hurley, K. (2016). The dark side of behavior management charts. The Washington Post, September 29, 2016.

Lawrence-Lightfoot, S. (2017). Quoted in the introduction introduction to Shalaby, C. (2017) Troublemakers: Lessons in freedom from young children in school. The New Press.

Brown, B (2012). Daring greatly: how the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent and lead. USA: Avery.

Koplow, L. (2002). Creating schools that heal: real life solutions. New York: Teachers College Press.

Margaret Blachly is a psychoeducational specialist with Emotionally Responsive Practice at Bank Street College. Her background is in the early childhood classroom, where she has worked as a bilingual and special education teacher in independent, charter, and public school settings. In addition to her work with ERP, she currently works as a consultant in a variety of school settings.

Noelle Dean is a mental health specialist with Emotionally Responsive Practice at Bank Street College. She also consults in the lower school at the Bank Street School for Children where she is affectionately called the “feelings teacher.”