We speak with high school science teachers and trans men, Sam Long and Lewis Maday-Travis, who have developed resources and trainings to help biology teachers develop gender-inclusive curricula. Science tells us that sexual and gender diversity is both normal and positive.

*Overview and transcript below.

References

To know more about Lewis and Sam’s projects, please go to sam-long.weebly.com, fishyteaching.com and transeducators.com.

Overview

00:00:54 Introductions

00:56-03:19 Experiences as LGBTQ high school students

03:20-06:15 As teachers, coming out as trans men to colleagues and students

06:16-11:13 Key elements of a gender-inclusive biology curriculum

11:14-16:26 Working to help make other teachers’ instruction more accurate and inclusive

16:27-19:38 How teachers respond to trans students’ lied experience

19:39-21:42 Relevance of Dewey’s ethical framework

21:43-29:21 Success stories in demarginalizing students

29:22-30:51 How teachers can develop this work

30:52 Outro

Transcription of the episode

Jon M: 00:15 Hi, I’m Jon Moscow.

Amy H-L: 00:17 And I’m Amy Halpern-Laff. Welcome to Ethical Schools, where we discuss strategies for creating inclusive and equitable schools and youth programs and help students to develop commitment and capacity to build ethical institutions.

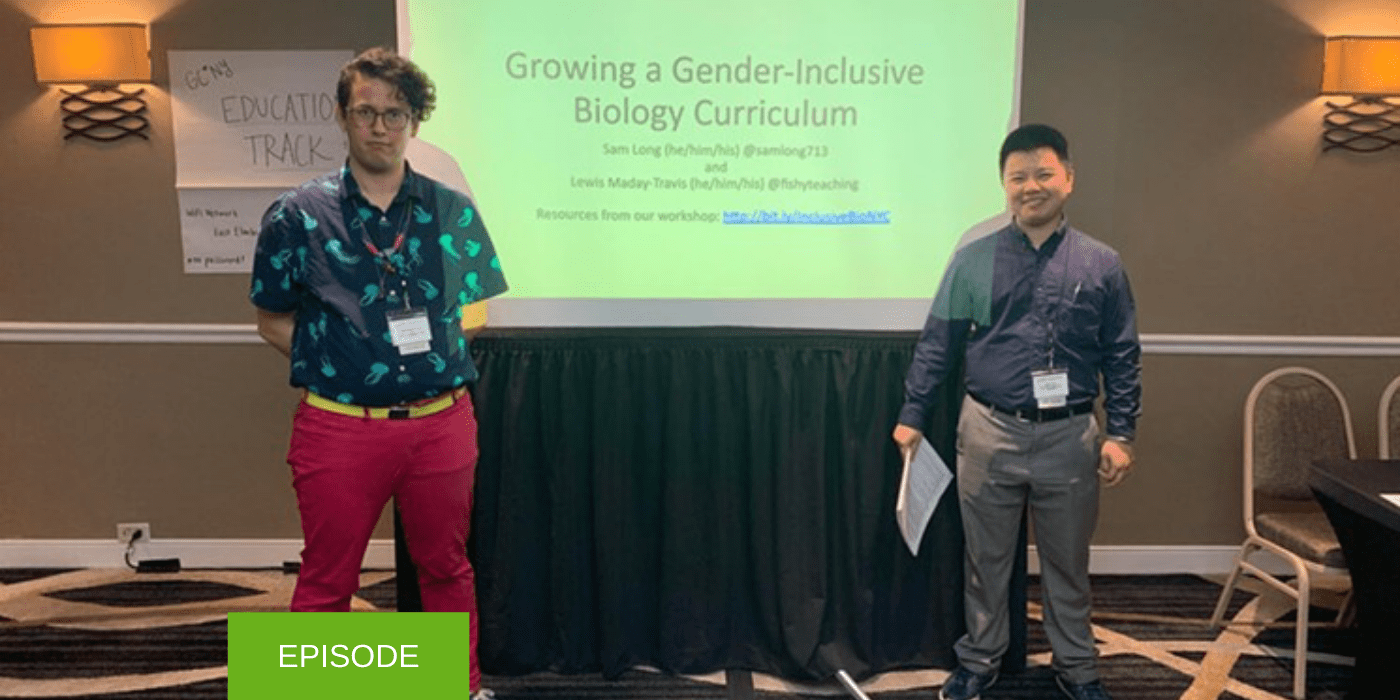

Jon M: 00:30 Our guests today are Sam Long and Lewis Maday-Travis. Sam and Lewis are both high school science teachers, Sam in Denver and Lewis in Seattle. Both are trans men. Since the start of this year, the two have been creating resources and providing training to help teachers develop accurate and inclusive biology curriculum. Welcome Sam and Lewis.

Sam L: 00:53 Thank you.

Lewis M-T: 00:54 Thank you.

Amy H-L: 00:56 So what were your own experiences as trans high school students?

Sam L: 01:01 Well, I could start on that one. My experience as a high school student was that I was starting to transition while I was in high school and not pertaining to science class, but in general most of the adults around me didn’t know what to do. It wasn’t something they had heard of. It wasn’t something they had had any training or experience in. And what that led to was some kind of poor decisions on their part and trying to figure out, well, uh, where should I use the restroom? How should I participate in overnight trips? And so that was only 10 years ago, but now we’re starting to see policies crop up and model policies be made available online for helping school districts to include trans students in kind of a standardized way or at least to have a guideline to follow in accommodating students. And then in the science classroom I learned nothing about it in health class they learned nothing about sexuality and gender identity. And one of my goals as a science teacher is to make sure that our students that are coming out now and identifying as LGBTQ see themselves represented in some way at school.

Jon M: 02:23 Lewis, did you want to add to that in terms of your experience?

Lewis M-T: 02:27 Absolutely. So my experiences were slightly different. For one, I didn’t come out as trans or I didn’t actually realize that I was trans until after leaving high school. And so most of my experiences around inclusion in high school were around identifying as queer. And I actually went to a high school where I was very well supported as a queer and gender nonconforming young person. And I think that the teachers that I had who really supported me have really been a model for me as a teacher about what inclusion and really knowing your students and really accepting them can look like. I will say that in terms of trans content or thinking about like trans issues or intersex traits or other kinds of gender diversity, I know that my school worked really hard to try to be as inclusive as possible and I know that folks made mistakes, which, you know, I think it’s also a good lesson for me as an educator bLewiecause heavens knows I make mistakes all the time.

Jon M: 03:20 So as teachers, how, and when did you introduce yourself to your students and your colleagues as trans men?

Lewis M-T: 03:30 I, um, I talked about this a little bit before with some people. So when I started teaching, I was not out as trans during the interview except that when I came in they thought that they were interviewing a female candidate. So it was kind of this funny thing where I did my whole interview day and like it seemed to go really well and it was like a lovely experience but was kind of weird around pronouns and things like that. And at the end of the day someone called me and was like, by the way, I just want you to know that I’m a man. I came out to colleagues right away at my previous school and folks were generally fairly accepting. I was the first out trans faculty or staff member as far as I know at that school and I didn’t come out to my students for a couple of years after that. And I think that a large part of that was both. I was working with young students, I was working with sixth graders at the time, but also just general attitudes and awareness around trans issues were significantly different. That was over seven years ago now. And I chose to come out to my students during a unit where I was leading them in thinking about identity in STEM so you know, who does science, why is it that some groups are over underrepresented in science, um, and told some of my own story as a trans person in science and my experiences and the response was overwhelmingly positive and I found that it allowed me to be much more myself as a teacher and also talk more about the justification for why I talk so much and work with identity so much in the science classroom.

Jon M: 05:04 Sam, did you want to add to that?

Sam L: 05:06 Yeah. My experience with introducing myself as transgender in my school has also been positive. I’ve come out to students and staff every year that I’ve been teaching, which is, I’m in my fifth year now and I’ve been very fortunate to have a supportive my school leaders and uh, have positive responses from students. I see my had an annually coming out as serving two functions. One, it’s how I’m most comfortable interacting with my students. Having them know that part of me and knowing that I am willing to support that part of them or any differences or identities that they may hold. And then the other function is as a form of setting the culture, the classroom setting a culture of inclusion and showing, uh, from the first day now, when I tell them about my identities, that we’re not tolerating any prejudice and we are all here to learn together and we respect diverse identities in our classroom.

Amy H-L: 06:16 What are the key elements of a gender inclusive biology curriculum?

Sam L: 06:21 So to me the key elements of a gender inclusive biology curriculum are approaches to teaching. And so it’s not teaching something new or separate. But in everything that I teach, I try to make sure that there is authenticity and what I teach. So everything is based on research, everything is accurate and modern science, everything is continuous. So we’re not talking about gender once or doing one big project and leaving it at that. The messages are consistent from lesson to lesson. And so students can feel a sense after the semester, after the year that well, you really touched on that and we developed these ideas in a continuous way. Another element is there needs to be affirmation of student identities. So we need to not just teach that there is diversity and living things, but that it’s a positive thing and not a disorder the way that it’s often talked about in genetics, not just an exception, but really the rule in biology is that there is diversity in the way that living things reproduce. And another key element of it is student agency. Students need to have a voice in what they learn about. And I’ve generally found that all students are interested in learning about ways in which biology represents gender diversity and sexual diversity. Um, but some students may have an interest in learning specific topics and so I try to start with gathering a lot of questions. What would students want to learn about before we start on a new unit where I know there’s going to be these opportunities to talk about gender diversity.

Lewis M-T: 08:14 I love that framework. I think it really fits the work that we’re doing and it’s also something that we’re trying to share with other science teachers as they are considering creating a gender inclusive biology curriculum. Um, I think for me the big thing it boils down to is they, would you mean to say and don’t lie. Like I’m really trying to create a space where science reflects the diversity that exists because in a lot of ways the biology that, that most of us are taught in middle school and high school is oversimplified and excludes a number of experiences including Sam and my experiences as a trans, as trans people.

Sam L: 08:55 Yeah. I think we could kind of, um, should I really put in an example when teachers are teaching about when one biology teachers are teaching about genetics, sex chromosomes, reproduction, there might be a tendency to start with what, what is canonical, what we already know. We’re going to talk about the XX and the X, Y chromosomes. We’re going to talk about the egg and the sperm and then to leave mentions of any exceptions to that, so called exceptions or differences to the end or of just to be mentioned. But as Lewis is saying that it is oversimplifying reproduction and not all species have two kinds of gametes, one bigger than the other, also known as the egg and the sperm. And not all organisms have this X, X, X, Y, sex termination system. For some organisms, sex determination is not based on chromosomes at all. It might be based on environment, like the temperature or the place in which life is occurring. And so to us, not oversimplifying, not only avoids referring to these stereotyped human gender binaries, but also pushes the rigor of what we’re teaching. So for example, when we’re talking about reproductive strategies in evolution, how do you pass down your genes to the next generation? It might be tempting to go with these very common examples. Um, birds, they’re monogamous, they mate for life, and it’s always usually always the case that the males are bigger and flashier in color. Then the females so that they can compete for a mate and then the females choose a mate and that’s something that you can teach. Everyone’s going to understand it. It kind of follows these human gender stereotypes of men have to compete for a date and then women choose, but it doesn’t do a lot to help students understand the core idea, which is that no matter how you’re passing down your genes, whether it’s through that female mate choice strategy or some totally different strategy, the functional thing here is passing down your genes.

Jon M: 11:14 How do you work with your colleagues in other fields to enable their teaching to become more accurate and inclusive of trans individuals?

Lewis Maday-Tra: 11:23 That’s an interesting question. There’s evidence that actually students explain encounter trans and queer inclusive content more often in the humanities than they do in science classes at a national level, and so Sam and my work has primarily focused on working with other science teachers and thinking about biology, science, health. I will say that I have collaborated with colleagues in other departments before to think about approaches to talking about gender, trying to include examples of people from history or characters in books, things like that that reflects diverse identities. But that’s more, that’s like, yeah, more in sort of a roll around equity in general at my school and less sort of the thrust of the work that we’ve been doing. Would you say that, Sam?

Sam L: 12:14 Um, yeah, the GLSEN survey in 2017 found that

Jon M: 12:18 I’m sorry. GLSEN for our listeners?

Sam L: 12:21 Um, so the GLSEN youth climate survey is, I believe it’s the largest national survey of LGBTQ youth and asks them about their experiences in school and outside of school. And one of, uh, things they ask about is, are you seeing positive representations of LGBTQ identities in any of your classes? And if so, what classes? And what comes up in the data is that most students, if they say yes, they’re reporting that it’s happening in English or social studies class and science among the lowest, I believe it’s 2% that are recording they’re seeing positive representations of LGBTQ identities in science class. And so that’s why we feel that our work is important, although it certainly can be integrated in other fields. And as well. Louis, when you were talking about working with other colleagues and other subject areas, ah, one thing I’d like to add is that any teacher can learn some approaches to working with diverse students such as asking them what name and pronouns they want to be referred to that make a really big difference in the lives of our students. And it doesn’t really have to do with any content area. There are a few ways to do that. You can do kind of a a paper survey or a Google form or just orally when talking to students join that you’re not going to assume something about their identity based on how they look or what it says their name is on the roster, but caring about what they want to be called.

Jon M: 14:03 So given what you’re saying about science being one of the lagging areas, what kind of work are you doing with other science teachers to try to get them to be more inclusive?

Sam L: 14:16 So since the start of this year, early 2019, the core work that we’ve been doing to work with other science teachers has been to give presentations at conferences and to publish essays about this work, about creating gender inclusive biology curriculum because we feel that that’s a core area where it’s like there’s underutilized potential in there. There’s so many topics in biology that you’re teaching anyway and it’d be very high leverage and high impact to rethink some of the language or rethink the way that something is taught in a way that will include your trans students, your gender diverse students, while also furthering their understanding of the topic. So we’ve put together basically, in line with our framework are five key elements of a gender inclusive biology curriculum. We’ve put together some, I’d say example lessons and non-example lessons that we have teachers in these workshops look over in small groups and think about them through the lens of this framework. Is this lesson authentic? Is there student agency in here? Is this using precise language? Is it affirmative of student identities? And we have students, I mean we have teachers. I think of where the lessons can be improved and they always naturally do a pretty good job with that, but identify things that can be improved about these lessons and that way we’ve been able to reach a lot of teachers. It seems that this work is kind of making the rounds, um, on the internet as well. And we’ve been really lucky to have it shared on Facebook and Twitter and we now have a listserv called the gender inclusive biology education listserv and we send out a newsletter once a month to teach us that or in the group with resources.

Amy H-L: 16:27 That’s fantastic. A question that comes up a lot in all sorts of sort of groundbreaking types of professional development, which is the teachers who come to your trainings and who are interested in this sort of thing are obviously the ones who are going to be open to modifying their curriculum and accepting of, uh, a spectrum of identities. So putting aside your, your own curriculum and trainings, do you find that most teachers in 2019 respond competently and compassionately to the lived experiences of trans students or does it still vary a lot?

Lewis M-T: 17:14 I think it’s been clear based on the conversations we’ve had with teachers at our workshops, that there is a really wide range of where folks are at. At a recent conference presentation that Sam and I did together, there were a number of teachers there who spoke about being first year teachers and being worried about losing their contracts if they bring up trans issues in the classroom because of parent backlash or because of administration being hostile towards those identities. Um, there are also a wide range of laws either supporting or not supporting educators doing this work. That varies state by state and sometimes district by district. So it is true that the folks that we are currently reaching out to are folks who are very receptive and excited about this work and that’s exciting for us. I think I, I know that for me, I hope that these conversations start getting boosted to the state and national levels because it’s really, really crucial that trans students receive more support than they’re getting because there’s a lot of evidence that trans students have a really, really hard time at school.

Sam L: 18:17 Yeah, I agree. And the teachers that tend to be interested in our work and come to our workshops, yes, they, there are teachers that already want to do the work whether or not they may feel supported in their schools or districts for that. Um, somebody pointed out at the previous conference that the audience tends to skew young, younger teachers, but I work in a big public high school where I’m by far the youngest science teacher. Folks who have been teaching here a long time and they’ve been receptive not only to my personal story and identity, but to my mission in changing the biology curriculum. Not that they’ve implemented it yet this year, but I tried to kind of drop it into the conversation anytime I’m doing something that I know that they’re probably not doing and say, well, this is research space. This is accurate, modern biology, this, you have no idea what great things this will do for your LGBTQ students. Just to hear you mentioning that because they notice, you think your students aren’t listening. They’re going to hear that and they won’t forget it, that you said something that affirms their identity or you said that chromosomes are not the only thing that make you a man or a woman. They need to hear that from their teachers.

Jon M: 19:39 The patron saint in a secular sense of Ethical Schools is John Dewey. Um, in what ways, if any, do you consider Dewey and his ethical framework relevant to your work? Is this something that you’ve thought about?

Lewis M-T: 19:55 It’s something I’ve thought about a little bit. Um, I don’t know Dewey’s work super well, but it’s my understanding that Dewey really believes that classrooms are not just a place where students receive information but also a place where they learn to become citizens in a community and really engage in a democracy in a really like participatory way. I would say that for me, trying to create a inclusive biology classroom and inclusive science classrooms, not just of gender identities and diversity but of many forms of diversity is a really crucial part of creating students who are ready to engage in the like beauty and mess that is American democracy.

Amy H-L: 20:42 Did you have something to add to that, Sam?

Sam L: 20:44 Just a little thing. I know that Dewey wrote about experiential education and that you need to, before you take something to be true and correct, it needs to be empirically proven. And I think that relates to some of the emphasis of our work because there are these accepted truths, um, in society that you’re either a boy or you’re a girl that’s immutable, gender is immutable, that don’t really turn out to be supported by the research in biology. And it’s quite a discovery for students to see that and to be faced with the research and to be faced with real diversity, the 10, 20 plus possible combinations of sex chromosomes you can have and still be a human when they haven’t learned that before.

Amy H-L: 21:43 So what are some examples of success stories you’ve seen where either through curriculum or academic discussions or through intentional relationships, teachers have been able to successfully demarginalize trans students?

Lewis M-T: 22:02 It’s so interesting that term, the marginalized I’m very uncomfortable with because I feel like there are so many ways, like I want to bring trans kids into the center. And also I think that the trans experience is it inherently marginalized in our society. So I’m like, Hmm. Um, I will say that I have had many students come up to me, not just trans students, grateful for the ways that conversations have been held and sometimes providing feedback about how to create more inclusive spaces. But I think that the relief and the sense of kind of being on the same team that I have had with some students who have marginalized identities, including trans students, has been really powerful. And those students have even come to me later and be like, “Hey, like I’m having this issue in my science class. Like I want to talk to you about it and I want to like work through it with you.” I’m not being very specific here. Sam, you might have some better specific examples.

Sam L: 23:03 Yeah, I could give an example. When I teach about genetics, one of the first lessons and conversations that we have is about the language that we’re going to use and whether that includes everybody. So we look at a couple of sentences, very common sentences like, “We get, we each get half our DNA from our mom and from our dad” or “Men produce sperm cells and women produce egg cells.” And these are things that they’ve learned in middle school, if not before that, somewhere in their lives. But I ask them to take a minute before answering and think “Does this include everybody?” And they are always able to come up with a huge list of people that it doesn’t include. People who are adopted. The people they call their mom and their dad don’t share much of their DNA. People with same sex parents, trans parents, people who are infertile. They don’t produce sperm or egg. Um, people who transition. And naming those things and specifically talking about how gay, lesbian, trans people fit into this, that they are still humans despite not following these rules, I think is really impactful to students. And what I generally see that to me is a big early indicator that, that this is affirming for them or at least starting to help them is they kind of perk up in class. They raise a hand more when they wouldn’t normally participate much in my class. And sometimes they breathe a sigh of relief like, okay, we’re gonna, we’re gonna learn about this genetics topic and it’s not going to be like it’s been before. It’s not going to be only about heterosexual, cisgender people and it might’ve been like that in their middle school science classes or their middle school health classes. And students talk to me after and say that, that made sense that I appreciate the way that you talked about that. Um, in my first year I had one student stay way late and wanted to talk to me about the way that theories for how primates can have homosexual behavior and how it could may contribute to the fitness of species in primates and I could just feel that he had never gotten to talk about this before in any other class and that’s something that was of interest to him. He identified as part of the LGBTQ community and the students will want to talk about this and they’ll want to learn about this if you allow them to learn about it in a safe way and a way that feels it is a part of the curriculum, it’s what we need to learn in order to understand the complex world around us. Lewis, did you have another example?

Lewis M-T: 26:05 Oh you just, you, I mean you did such a good job there. I would say that the thing that came to mind for me actually, especially related to how these conversations changed student perspectives and try to do that work of demarginalization is last year I was teaching a unit where we had a lesson about intersex traits and we talked about the prevalence of intersex traits, which you know the numbers vary between 0.5 to maybe 2% of the population and a student who does not identify as in the LGBTQ umbrella as far as I know, was like “If it’s that few people, like why does it matter?” And like having that conversation with students because I think that’s something that sometimes comes up for people where when talking about folks in the LGBTQ umbrella, like because we are not a majority group, they’re like, well but does it really matter? Like we can just, you know, meet the needs of the majority. And I was able to talk about my experiences as a trans person in science classes and also wanting to see myself represented and knowing that there are many different forms of diversity that may not be that common but are really important to understand. And I think that that conversation was a way of like doing that work of centering what is considered other and actually just treating it as a part of the natural diversity of what exists out there.

Sam L: 27:30 I would love to quickly add onto that. Yes, it’s a common comment that I hear, that this is a small number of students we’re talking about, we’re talking about a really small group of people, but things that are uncommon, that has nothing to do with how they’re regarded in society. There are genetic traits that much less common than intersex traits. Something that’s kind of been over YouTube lately is this super color vision gene for types of cone cells. And there’s all these tests to see if you can have it. It’s really rare. It’s regarded as something good. You can see more colors than everybody else. And one conversation that I have with students when we’re talking about genetic traits is that we need to be reflective about what we’re calling a disorder, a disease, a variation, a difference. For example, why students are, they have a lot of thinking to do when I present them with this idea that well, a red hair is caused by a genetic variation, a genetic mutation. So are some of these intersex traits. What’s the difference? Why was one called a disease or disorder for so long? And they’re quite surprised to learn that red hair, that gene is actually associated with some statistically significant, worse health outcomes due to a resistance to anesthetic that apparently it makes you 20 times more likely to die under general anesthesia due to resistance to that general anesthetic. So what we’re treating as a disadvantage or merely a difference or a positive difference, there is no gold standard for that. That is completely determined by society, what we’re calling a difference versus a disorder.

Jon M: 29:22 Is there anything you’d like to add that we haven’t covered?

Lewis M-T: 29:24 I think one thing that was really powerful for me in a conversation that Sam and I had with Ashes Amenic, another person doing this work but at the undergraduate level, um, is that there can be this idea that if you don’t have an encyclopedic knowledge of LGBTQ issues or if you aren’t an expert or if you are going to make a mistake, that it’s better to not try. And I would say that there are very small moves that you can make as an educator that can really make a difference in the lives of transgender, nonconforming and intersex students, including just being like, Hey, like we have this textbook. The textbook is not perfect. Let’s learn about this together. But like my apologies, but we’re going to go with it because you know heaven’s knows that us teachers don’t have months and months of paid leave to write beautiful gender inclusive curricula and materials that are going to reflect exactly the identities of our students and so you know it’s messy dive in but also don’t feel like you have to do it all at once.

Sam L: 30:28 Definitely. This is a, an emerging topic really. There is no textbook that it’s going to help you do this work right now and it’s so, so individual relative to the class and the teacher that I can only encourage teachers to dive into the messiness of it and to be a part of the development of this work. Right.

Amy H-L: 30:52 Well listeners, you can find links to Sams’ and Lewis’s inclusive biology curriculum resources on our website. Thank you so much Sam Long and Lewis Maday-Travis,

Jon M: 31:04 And thank you listeners for joining us. We’d like to hear how you’ve incorporated ideas you’ve heard on our podcast or read on the ethical school’s blog. Also, if there are topics you’d like to hear more about, let us know. Please email us at hosts#ethicalschools.org. Actually, I’m pleased to say that that’s how we met Sam and Lewis. You were the first people to email us at that particular email, so thank you. We also offer professional development for schools and afterschool programs in the New York City area, and you can contact us for details. Check out prior episodes and articles on our site. We’re on Facebook and Twitter @ethicalschools and Instagram Our editor and social media manager is Amanda Denti. Till next week.