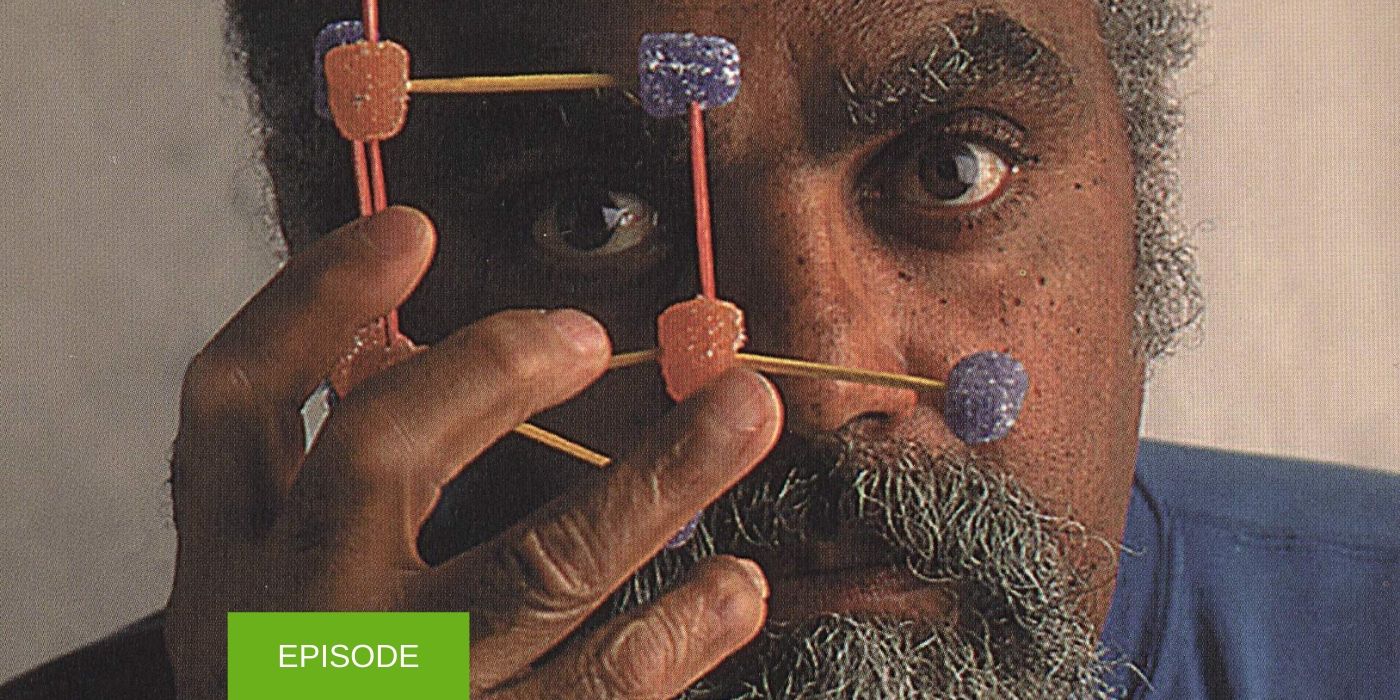

The Algebra Project founder and president–and lead organizer of the famous 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer voting rights campaign–talks about math literacy as an organizing tool to guarantee quality public school education for all children. Bob Moses describes the Algebra Project’s strategies to connect math to students’ life experiences and everyday language. The interview is divided into two episodes.

*Overview, transcript, and links below.

References

- Part two of this interview with Bob Moses.

- Book Radical Equations: Civil Rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Project by Robert P. Moses and Charles E. Cobb

- Book Slavery by Another Name The Re Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II by Douglas A. Blackmon

- About Circular #3591

- About United States x Louisiana

- About San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez

- Ethical Schools: Mark Santow on Suing Rhode Island For Educational Equal Protection

- Ethical Schools: Kate Belin on The Algebra Project

- The Algebra Project website

Overview

00:00-1:08 Introductions

01:09-14:58 Math literacy as an organizing tool; experiential learning; Willard Van Orman Quill’s “regimented language”

14:59-16:39 Literacy across the curriculum

16:40-20:28 Logistics of working with schools

20:29-25:42 Bottom up movement; involving students and parents

25:43-32:02 Funding as a critical issue: District 13 in Brooklyn, Miami/Broward County; need for direct federal investment

32:03-48:09 Quality education as a Constitutional right; Who are “We, the People?”; Circular 3591; Douglas Blackmon, Slavery by another name; equitable funding

48:10-50:08 STEM funding, National Science Foundation (NSF)

50:09-end Outro

Transcription

Amy H-L: 00:10 Hi, I’m Amy Halpern-Laff.

Jon M: 00:17 And I’m Jon Moscow. Welcome to Ethical Schools. Here’s Part 1 of our interview with Bob Moses.

Amy H-L: 00:24 Our guest today is Bob Moses, Founder and President of The Algebra Project. During the civil rights movement, Bob Moses was field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee or SNCC. He was co-director of the Council of Federated Organizations, COFO, which was the umbrella organization for civil rights organizations in Mississippi and the main organizer of Freedom Summer, dedicated to registering black voters, as well as a key organizer of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. In 1982, Bob was awarded a MacArthur fellowship and used the money to found the Algebra Project. His book Radical Equations connects his voter registration work in the 60s and his focus on math education as a tool for organizing. Welcome, Bob.

Bob M: 01:08 Thank you.

Jon M: 01:09 The Algebra Project website says that the Algebra Project “uses math literacy as an organizing tool to guarantee quality public school education for all children in the United States.” What does that mean? How do you use math literacy as an organizing tool with impact beyond the math classroom itself?

Bob M: 01:29 Right. So the math classroom, of course, is actually an important part of this idea of using math as an organizing tool. The basic idea was born during 1961-62 in Mississippi around monthly meetings where people got up early in the morning to come to Jackson, some as early as 4:00, 4:30, and the discovery that we needed to abandon the traditional mode of having some kind of platform where people spoke and everybody listened. So what we did was when they came in, they had to sign in to a problem and the field secretaries gathered the issues and problems as they were, you know, working around the state with people and everyone had to sign in on a particular problem they want to work on. And so the meeting was in local groups or issue groups focused around a particular problem and they had to figure out what they wanted to do about it and when they came back the next month, report out. So, so that led to a real participation. I think the word was participatory democracy. We didn’t actually call it that. But that’s what we were doing. So the math class is traditionally a class where the students themselves are disempowered and they sit and listen to an expert, who is the teacher or someone. And so what we set about in the Algebra Project was developing a curricular process to flip that around, right. And, I did my work in philosophy of math and I don’t think I would have come across thinking like this if I had done my work just in math. And at Harvard in the 1950s, Willard Van Orman Quine was the star of the Harvard’s philosophy department and he was also a mathematical logician, and he took an interest in the issue of language and mathematics. And what he said was that elementary arithmetic, elementary set theory, and elementary logic get off the ground by what he called the regimentation of ordinary speech. And that this regimented language was really nobody’s spoken language. It was just a form of artificial speak, which was an intermediary between the spoken languages and the actual symbols that are found in the math and science textbooks. So the idea, that idea, kind of grabbed hold of me and it actually came to fruition when I was teaching at the open program in Cambridge in the 1980s and I had a young fellow who wanted to do math, he didn’t know his multiplication tables and he wanted to be with his friends who were in the Algebra Project. When we came to a number line question, I saw that Ari was answering some question, but it wasn’t the question that the author had in mind. So I first figured out what his question was and basically Ari had a “how many” question and that he had started from how many toes and how many fingers, right. So I said to myself, well, Ari needs another question, right. And I thought a lot about it and then finally I said, well, he needs a “which way” question. And as soon as I thought that, I said Ari already has a “which way” question. Ari knows which way home, which way to the mall, which way to the subway, all of that. What he needs is a “how many” question together with his “which way” question around his concept of number. Right? So this turns out to be a huge leap in students’ progress towards algebra, right, that at the beginning of it they have to deal with a different concept of number. And so then the question was, well how do we put those two together? And so then Quine’s insight came. I was looking and thinking about what Quine said about language and the regimentation of it. And one day I was walking down in Cambridge getting into what they call the Red Line and it’s a subway stop, and on the outside was the answer to a “which way” question, which is inbound. On the other side of the street it was outbound. So yeah, I had a vehicle for putting the two questions together, the “which way” question and the “how many” question. And we developed a concept called the trip line, which is not a number line. It’s still a mathematical object. It just doesn’t have certain features that the number line has. But it’s a tool which you can introduce movement numbers. That is numbers which have two features. One is “which way” feature. And the other is a “how many” feature. So you’re going inbound, three stops, or you’re going outbound, two stops, right. So this led to a curricular process in which the student now is put at the center, just like we tried to do in Mississippi with the sharecroppers, right. So we embedded this in what is called “experiential learning.” And that model, you know at 12 o’clock you have an event, and the event in this case, well, the students take a trip and they prepare for the trip and they can sketch objects, they can take their photos, they can write, and when they come back they write about what they observed on the trip and that part belongs to them, right. It doesn’t belong to the teacher . It belongs to them. And then we ask them to identify, well what are some features in what you wrote, right. So typically students will not identify what we think of as mathematical features. And partly the reason is mathematics tries to formalize what’s obvious. And so by definition, you don’t really pay attention to what’s obvious. You just, it’s obvious, so there it is, right? So every trip has a start. Well that’s obvious, so you’re not going to mention that as a feature of the trip, right, as a particularly exciting feature of the trip. But it’s an important mathematical feature, right. Every feature has a finish. I mean, every trip has to finish. You stop someplace and get off, right? That’s obvious, too. So then what we did was once the students are identifying what they think are of important features, they’re open to suggestions about other features, right? And so we then asked them to write what we call the talk, which is an example of Quine’s regimented language. And so feature talk is not anybody’s spoken language, right. An example of might be, how tall are you, Jon?

Jon M: 10:12 Oh, about five six, five seven. And I’ve shrunk.

Bob M: 10:12 Five seven. Okay. And Amy?

Amy H-L: 10:19 I’m about five five.

Bob M: 10:23 Okay. So we can say, well, Jon is taller than Amy.

Jon M: 10:27 For the moment, yes.

Bob M: 10:30 For the moment. And so the question is how do we know we’re talking about height? In other words, what in the sentence “Jon is taller than Amy” clues us into the feature of Jon and Amy that we’re talking about, which is their height?

Jon M: 10:48 Taller?

Bob M: 10:48 Taller. Yes. And if you ask about the syntax of that sentence, you have two names, Jon and Amy. Then you have some words, “is taller than,” right. And however you describe that set of words in terms of your grammatical categories, the feature, the mathematical feature that you’re interested in, resides in those words “is taller than.” Well, math won’t let you have a symbol for “is taller than.” It just doesn’t have a symbol for “is taller than.” So math then writes feature tall, it introduces the feature height and it says the height of Jon, blank, blank, blank, the height of Amy. So what is going in the blank, blank, blank? The height of Jon, blank, blank blank, the height of Amy.

Amy H-L: 11:43 Is greater than.

Bob M: 11:48 Yes, exactly. So there’s nowhere in the logic and the grammar which teaches you to make such a substitution. Nobody ever learns that in the grammar lessons in school. But you acquire that as you acquire, I suppose, sophisticated language, right, cause it’s not just math that’s going on in all disciplines, right. So it involves a shift in where you locate the information. So it’s taken out from a particular part of the syntax and put into the name. So we teach the kids how to do that. And so they write, they can write feature talk. Now the feature talk, the height of Jon is greater than the height of Amy can go right over into symbols. All you need is a symbol for height, a symbol for greater than, a symbol for your names, right. So that symbolization, you are already now into mathematical symbolization. But the crux of the matter is the move from what Quine would call ordinary language to regimented language. And his point was that all of math and all of science really gets off the ground by regimented language. Now the linguist, Quine, was writing in the 1950s. The linguists at the turn of the century began to pay attention to this. And they call this a grammatical metaphor that this is different from just the metaphors which deals with just words, right. So that’s at the heart of this, right. If you think about Mississippi, how do you get the sharecroppers themselves into the conversation about what it is they’re doing, what they want to change, and how to change it on little things. And so if you can get the school system and the teachers and the principals to agree to free up time because this can’t be done, right, just snap, snap, snap like that, then you can begin to get the students into a kind of meta position vis a vis mathematics. They are actually looking at events and figuring out how to talk about those events in their own language. And so here, it doesn’t matter that you don’t speak the King’s English, right. It’s not the King’s English that really underlies the mathematics, right. It’s the regimented language, which is nobody’s.

Jon M: 14:59 I have a question on that. I mean people talk about literacy across the curriculum and when you’re talking about, sort of, the words that exist in the regular language versus in the regimented language, is this something where in schools that are using the Algebra Project that the language teachers, the English teachers, get involved as well so that students are introduced to those concepts in multiple classrooms?

Bob M: 15:25 Yeah. So that’s, that’s a big, big, big question. And I’ve watched different scenarios play themselves out cause it depends on who’s teaching, who’s running the school, what exams that the kids have to take. It just, you know, it just depends on the local circumstances, but it does open up this possibility, right. And I’ve been in some schools. There was a middle school, Brinkley Middle School in Mississippi where for a couple of years both the language and the math teachers worked on the curriculum using, looking at this phenomena, right. So we have, we do have some contact with the Writing Project in different places, but there’s nothing systematic at this point about doing what you just suggested. But it’s there, it’s, it’s available because math, of course, is the place where the whole issue of language and how it operates is really not attended to.

Jon M: 16:40 So let me just follow up with that because obviously a problem that huge numbers of programs have is that they want to go into a school, they want to work with a school. And so some of the questions that come up, but I’m just really curious how, how you’ve dealt with this over the years. I mean, one question is, you know, whether all the teachers in the school have to buy in or whether it can be done or started with those teachers who are most enthusiastic. And then a followup question is how do you cope with these kind of inevitable changes in leadership priorities, all of these kinds of things, as you’re doing this in so many different districts with presumably different philosophies and different environments. Just as a, almost a logistical question.

Bob M: 17:26 Yeah. So I haven’t been in any school where all the ducks have been lined up, in other words, all the teachers, the administrators who oversee the teachers, the principal who oversees the administrators, the downtown people, and then in any situation where they’ve all lined up. So in practice, you’re dealing with trying to set examples, through a few teachers and the principal, you need the principal’s buy-in, right, to do this. So that’s basically how it’s happened. And then, in a district, they will look for principals and then the principals will look for teachers, right. So if the principal says, I want to, yes, we need to do this and then he looks for which teachers he thinks, might begin to do it. So we’ve just been in a lot of different kinds of situations. Basically the strategy being that you’ve got to keep working the problem at the ground zero level where the problem exists with the students. We’ve learned a lot doing that. And then the question is, well, how do we actually get the resources so that this can actually be carried out because you know, just the simple thing of taking a trip, right, or having a summer induction. I mean, we’ve gotten some evidence that if you start with rising ninth graders as they leave middle school and in the summer before, have a six-week induction with them and their teachers, right. And then follow them through their ninth grade and then another summer program between ninth and 10th and then their 10th grade that those coming into high school performing level one, you can get them up to where they need to be by the end of their sophomore year. But you have to be freed up to do this curricular process with curriculum materials like I was talking about.

Jon M: 19:52 And then you find that they can maintain that even if there’s no followup in say 11th and 12th grade, that that there’s a carryover effect?

Bob M: 20:00 Yes. Right, right. As they go into 11th and 12th grade. But also, I mean, so 11th and 12th grade you’re back into more traditional curriculum. But they are able now to make that transition, having gone through this process. So that’s, that’s one little chunk, right, that we have some evidence about.

Amy H-L: 20:29 Bob, going back to what you said about participatory democracy as an impetus for the Algebra Project, the project is by design a bottom up movement, so it would be spearheaded, I suppose, by families and communities, perhaps students as well. Once it’s implemented and essentially institutionalized, how do you maintain that grassroots quality?

Bob M: 20:57 So bottom up is what we aim for. It’s been very difficult to establish, to actually get communities, their parents involved. We went in a Haitian American high school in Miami, Edison, when Rudy Crew was superintendent of Miami and he gave us a high school. We went and talked to him. So we wanted to show, we wanted to follow one class for four years. So they had an algebra teacher and we, myself and a graduate student, the issue was that they had an exam to take. These were ninth graders entering with level one proficiency or whatever you call it. And they put them all in one class. And then one thing we were able to do ,what we decided was, look, there’s no way to go. Just cold turkey in here and you know, [inaudible] around, well we need to do is get to know the students. And so we went every day and sat in on the class and just helped them with whatever the Algebra Project teacher was doing. And he was doing it three days a week and then the other two days they would go to a remedial class to a different teacher. So we suggested that, well, why don’t they have the same teacher every day. And so the school actually did that. They put them through. When we got to know them well enough, we started to going to their homes to visit and talk with their parents. And by the middle of the school year we were able to call a meeting of them and parents in this class, right, and explain to them what we wanted to do, that we wanted to follow your students for four years to high school. And this was mostly mostly Haitian Americans. There were some African Americans. So that summer we were able to offer a six-week induction at Florida International University where they actually came and lived on campus, the whole class. So this made a huge difference both in their understanding of what they were being asked to do and their ability to relate to each other around this work. And so that class, we followed them through for four years. They had three principals in four years. The second principal said that he wanted to shut them down. They were going into their junior year. They organized, the students themselves, organized and won that they should stay together as a class in their junior year. And we had a mathematician who would come in and work with us during this time, Dubinsky and myself. And then the third principal came in and split them up in their senior year. But what kept coming together was an after-school program, the Young People’s Project, which is a spin-off of the Algebra Project. So they had started working with them and they were paying them as math literacy workers and they were running into a couple of the local elementary schools after school and working with them. And they continued to do that during their senior year and all but one of them passed all their classes and graduated on time. So, I mean, if you just think of that, the kind of work that takes and the resources, and the country is not interested basically. It doesn’t have any real source of funds to do this on any, to any scale. But it’s, it’s what needs to be done. It’s part of what needs to be done. So I’m just saying that the community organizing part of the work has been really as tough as going into the schools. You can’t get the parents out, but you again, you know, you need the cooperation. In Brooklyn, we were in Brooklyn in I think it was six, and the superintendent was Young. I think he was related to the jazz musician.

Jon M: 25:43 Oh, Lester Young. Yeah. Yeah. He’s a regent now.

Bob M: 25:46 Yeah. So you said, well.

Jon M: 25:48 District 13, I believe that was, that was it. In fact, one of our board members, Shirley Edwards, worked on the Algebra Project and I believe it was in that district with him.

Bob M: 26:00 So he says to us, well, we want to, we say we want to start in at least one middle school. So he says, well, show us that there’s demand for this, right. So I said, well, help us. We will do parent nights. So he sent out, you know, notices to parents who were coming to this school and we began doing parent nights with them. They came in. As they came in, we had the Young People’s Project and other at workstations, and they would go right away to some workstation and do some things that we had set up, right. And then we would have a discussion about what they did afterwards and we would ask them if they wanted to sign on that this should be introduced into the school. Well that went fine until we got too many people who said they wanted to do it. And so the school system then can’t handle the demand, right. But they don’t go up the ladder and say, look, I’ve got this demand. I need resources so I can meet the demand. No, they shut the demand down. They stopped sending out the notices. So we started but, and we had, you know, a teacher, we got kicked out of there when, what was the Yale psychiatrist, Comer. Yeah, he got 50K from the Rockefeller Foundation, I think. I’m not sure remember that. And a part of what he did was focus on district 13. And then of course he has a whole program that involves all kinds of meetings and workshops and everything. So there’s not time to do both. And so we got pushed aside then. So it’s just saying that the issue of actually reaching the community with the school requires that the school be open to bringing in the parents, not just, you know, for pro forma PTA meetings or something, but to actually sit down with students. So like in Miami now in Broward County, we’re negotiating with them, we have, I think they have four high schools, which are doing the Algebra Project. And we’re negotiating with them around making schools. But one problem is how do you get the students in the middle schools who are going to these high schools to buy into this before they begin because we need them in the summer induction, right. Well, that means money. It means organizing with the school’s parent nights on a regular basis and we come in and show them math and talk to them about what it is we want to do, right. But you need to do that in cooperation with the schools. It won’t work if it’s in opposition to the schools. So one of the things we’ve been looking at is, well, I’ve been rethinking my experience in the 60s with the Justice Department. So if you think of the 1957 civil rights bill. Eisenhower was president and Johnson was the majority leader. So it was the first time since Reconstruction really where there was direct federal investment involvement in this kind of problem. It was focused on the right to vote. But what it opened up was the idea first with a department, civil rights division of the Justice Department, and second with a new assistant attorney general, is that [inaudible] for civil rights. So when John Doar appears at the doorstep of Steptoe in Amite County, who is the head of the NAACP in Amite County, this is a very different situation, right, where you have direct federal investment and involvement in what’s going on. And so, we had our first meeting in DC last summer, trying to work to get an alliance of schools, and the Fannie Hamer school is part of this to figure out, well, how do we actually get attention to and consciousness of and resources for this problem, focused on the math and on the students who aren’t making it through the system. So I think we, we need to keep, we need to relook at the issue of direct federal investment and involvement in at least one corner of the problem, right. I don’t know that it’s even feasible to think about say, well, the whole shebang. But we might be able to actually convince people that we need this for math, for literacy at this level. Students who are not currently making it through. And we have enough kind of anecdotal evidence from around the country over the last almost two and a half decades. So there’s something there to, you know, you’re not doing this on an empty stomach, so to speak.

Amy H-L: 32:03 So it sounds as though you’re talking about quality education as a constitutional right. Can you talk about the campaign for that and what concrete results you’re hoping to achieve?

Bob M: 32:15 Yes. So I think one thing is to focus on the Preamble. I mean, the country is, you know, going through its really issues now, but the Preamble, the idea that “we, the people” really are the people who own this Constitution and it lists a set of common goods that the Constitution and we, the people should address, right. And it raises the issue of, well, who are members of the we, the people class, right. Of the Constitution and how has that evolved over the centuries. So I began with white men who own property. And the real delineation, if you like, comes by comparing the Preamble with Article four, Section two, Paragraph three. So you read Article four, Section two, Paragraph three and what it establishes there is another class of constitutional people, Africans as constitutional property, right. So the Constitution actually elevates kind of abstract objects, right, constitutional people on the one hand, constitutional property on the other hand, and yet these corporations as people, so it elevates kind of abstract objects, right? And what has happened across the centuries is that the abstract object of who the class of we, the people has expanded, not continuously because it’s also contracted, right. So the latest expansion, of course, was in 1965 as part of really what the country went through around the civil rights movement and the idea that now this was a country that was really wanting to pursue equality in some dimensions, right. Different dimensions. And so now you apply that to immigration, right. And so they roll back the laws that were put in place in the 20s, right, the 1920s, and opened up the doors in immigration. But, and what we have now, we have two kinds of deportation going on in the country, one which gets a lot of play, which is external deportation. People who are coming and want to be citizens. The other, which gets not so much play at all, is internal deportation, right, the rounding up of young black men and other ethnicities and sending them to jail, right, mass incarceration. But so, but this raises the question, both those deportations, right, and the struggle around them raise the question of the Preamble, right. The reach of we the people, who was going to be a member of that class. And with respect to education, it’s just been that African Americans, first when they were just Africans and then second when they were second class African American citizens. And then even in this age now which I think of as a kind of a third constitutional age where, so in the first age, they were property and you don’t park it, you put it to work and you insure it and mortgage it, but you don’t park it in jail. So there were no Africans in jail. Then in the second age, African Americans got rounded up. You remember, do you know Circular 3591?

Jon M: 36:31 No, I don’t.

Bob M: 36:34 Yeah, you can google it. Circular 3591. It was Attorney General Biddle, I think is his name, Roosevelt’s attorney general. He passed it in December 12th, 1941, five days after Pearl Harbor. And basically Roosevelt had decided he needed young black men to fight his war now. And so this circular says, stop rounding up young black men for vagrancy and penury and being poor, and treat their cases as involuntary servitude or slavery. So this kind of officially brought an end to the practice of rounding up tens and tens of thousands of black men. Blackmon, I think his name, has a book, Slavery By Another Name. You know that book?

Amy H-L: 37:29 Yes.

Bob M: 37:29 And that’s how I came across this idea, came across this circular cause it’s the foundation. He’s a really interesting person for your broadcast because he himself, uh, was born in the Delta in Mississippi. He was raised in a little town right next to Leland, right next to Greenville and he was born in ’64 and so hit the first grade in 1970 when Mississippi and the South was ordered, you know. “Deliberate speed” now means you’ve got to start to integrate. But his parents had some kind of consciousness and also didn’t have money and they sent him to the regular school. So he went to school with the black kids and when he hit the seventh grade, for some reason he decided to write about Strike City, which was a place where people who were sharecroppers on a local plantation had struck and left and set up a camp, which they called Strike City. So he wrote about it and he got an affirmative action prize. They gave out two prizes, one to the black school and went to the white school. So they thought he was black because he was coming from the black school. But the next year his mother and the teacher said, well, you should give this talk to the Rotary Club. He did. And one of the nightriders who used to ride by and shoot into the camp was then came after him. So he understood that it wasn’t just history, he was looking at this. And then he went and through college worked for the Wall Street Journal. He was in Berlin when the wall came down and he got an idea. What if we look at American corporations in the same way we look at German corporations vis-a-vis the the Holocaust, and look at American corporations vis-a-vis African Americans in the South. And so he wrote his article. It was on the front page of the Wall Street Journal and his whole life changed because he got thousands of letters from people talking about their uncles and grandparents who had been caught up in this system. And so he did his research for his book, not like an academic, you know, not going to libraries and so forth, but actually going into courthouses and rifling through all those papers and everything. So that’s where we were in what I think of as the second constitutional era, the era after the civil war and before the civil rights movement, right.

Jon M: 40:19 I just have a question about Circular 3591 was coming right after Pearl Harbor. Was it then that the idea was to, instead of rounding up young and older men for jail, to push them into the military for the war?

Bob M: 40:38 Right. It was about needing young black men.

Jon M: 40:41 Oh, we’re definitely going to put that link on the website along with the podcast. But please go ahead with what you were saying. You were saying that that was the second and then…

Bob M: 40:51 I mean if you think about it, the first constitutional era, we are operating with constitutional property as a constitutional concept and Africans as constitutional property, right. You have a war about that. And after the war we decide, well, we’re not going to have any more constitutional property, but we can’t quite agree that the African Americans now should be first-class citizens, right. And the question is, will the federal government actually ensure their civil rights and the Supreme Court decisions in 1883, right. You had the civil rights cases and then you had Plessy and then you have the Louisiana case. So the Supreme Court said turn this over to the States. And what’s interesting is that in the first constitutional era, it wasn’t the state that got protected by the federal government. It was the property owners, the we the people class. So if their property decided to own itself and move, they wanted the federal government to help them fetch it and go back, right. So you had those fugitive slave X, right. So that changed once we no longer had constitutional property and now the idea was that the state should regiment the lives of the African Americans. And of course with Plessy, that became actual legislative, constitutional and the civil rights movement upended that. And in some sense as the upending begins with WWII. If you think about what’s going on in the 20th century and the whole effort of colonial people to get some kind of political voice, that after it actually hits this country with the civil rights movement and in some senses is successful, that African Americans, this kind of internal colony, actually began to get a political voice after the civil rights movement and the 1965 voting rights act. Are you familiar with Wisdom’s decision, US vs Louisiana, 1963?

Jon M: 43:20 Yes, but why don’t you describe it?

Bob M: 43:21 Yes. So the thing in that decision, this is the Justice Department now going after states as opposed to just individual registrars, right. I mean, and there’s an analogy with how we do funding for education. So it’s individual cities and towns, right, where the funding resides. And for voting, the decision resided in the individual registrar and so they were going registrar by registrar with their suits and then they decided to do a whole state. They did Mississippi and Louisiana, and Judge Wisdom, who was on the fifth circuit, presided over a three-judge panel for US vs Louisiana, and in it he said, I haven’t seen it any place else, that the Southern wing of the Democratic party was the manifestation of the will to white supremacy and had been operating at such since 1875 right down to 1963 when he was writing his proposal just a month after Kennedy was assassinated. So the idea that within the country, the political force in the country was in line with all these court decisions and everything and the subjugation of African Americans for purposes of both education and, you know, voting. The two were connected when I was on the witness stand in 1963 in the spring, and it was before Medgar was assassinated in June. We had been demonstrating in Greenwood and that we got arrested and Burke Marshall was Assistant Attorney General. He filed suit and we moved our cases to the federal district court in Greenville and Judge Clayton sent John Doar to be our lawyer, and Judge Clayton had only one question for me. He wanted to know why is SNCC taking illiterates down to register to vote? So sharecropper literacy was the subtext of the right to vote, and anyone who came to us and said, well I want to vote, we didn’t ask them whether they could read or write. We just said yes and went down to the courthouse. So the idea of sharecropper education got really embedded in after the, the decision in San Antonio versus Rodriguez, in Texas, where they said, well you really can’t come to the federal courts for equity relief because there’s no substantive constitutional right to an education. And then you have, you go to state by state, you have that case in New York

Jon M: 46:24 Campaign for Fiscal Equity?

Bob M: 46:26 That one.

Jon M: 46:27 And now there’s the federal case. We actually had an interview about the federal case in Rhode Island where they are going to federal court and they’re saying that there is a constitutional right to a civics education because Rhode Island, both through its funding and through its failure to have a serious civics curriculum, specifically Providence, is failing in its constitutional duties. And we interviewed Mark Santow, one of the plaintiffs and his son is involved. He was saying that they hope to win obviously, but even if they don’t, that it will be a major breakthrough because it will be bringing it to the federal courts as opposed to simply, like Campaign for Fiscal Equity, which was saying that under the New York State Constitution they were failing to provide an adequate education. But I have a question that I wanted to ask in terms of the federal role and and the We the People campaign. So what would, and the idea that you were mentioning of beginning by focusing on math in particular as a kind of entryway. So I guess the question is what are the specific things that you’re asking for in terms of both a recognition of it as a constitutional right and then the implementation of it. And I guess a subtext to that is that right now there’s so much focus comparatively on STEM, on science, technology, engineering and math. Does this help as an entryway and are the directions that you see the movements around STEM going in, are they good directions? Do they address central kinds of issues?

Bob M: 48:10 Well, you have a problem. It did help in the sense that when NSF put out this RFP about STEM, we applied and we got a grant and basically, we said we want to form a national alliance, right, and we want to do this kind of bottom up. And then they, of course NSF, it’s had its problems with its funding, but they funded I think five alliances. But you look at them, they are all university-based, and of course NSF is a research organization. And so it, you know, pretty much partners with universities that are research organizations. But we’re going back to them, what we have to do is also mount a campaign which says this needs to be approached also from the level of the schools and the community, right, because there’s no funding currently through that program for any schools, right, indicate who [inaudible] and it’s, it’s all through the universities and they have special things they do to get people into their universities or, you know, into the workforce. But they’re not working in schools, right. So, so we are still working with, with that, right, trying to get NSF to come along with this idea. So that’s one thing.

Speaker 5: 49:54 Bob, I just want to clarify for our listeners, NSF is the national science foundation, and I believe that is the grant giving organization for many of these STEM projects, right? Correct?

Bob M: 50:07 Yeah.

Jon M: 50:09 Thank you listeners for joining us. We’ll be continuing our conversation with Bob Moses next week. Check out our website, ethicalschools.org for more episodes and articles. We’ve begun to post annotated transcripts of our interviews and we offer professional development in New York City area on social emotional learning. Contact us at hosts@ethicalschools.org. We’re on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Our editor and social media manager is Amanda Denti. Till next week.