Lindsey Dixon, Director of Career Readiness at Urban Assembly, talks about helping students make more informed college and career decisions. The current model is restrictive and outdated, leading to suboptimal outcomes for the majority of students. Hands-on experiences and self-reflection programs can help young people better prepare for fulfilling careers and lives.

*Transcript and overview below.

References

Overview

00:00-00:54 Intros

00:55-02:28 “Very restricted model” of college and career pathways

02:29-04:10 What should students be thinking about for their future?

04:11-08:11 College completion rates; college as “a risky business”

08:12-10:21 Ethical questions

10:22-11:53 Schools’ responsibilities in helping students think of individual well-being and the common good

11:54-15:11 “the leaky pipeline”; summer melt; impact of finances and familiy responsibilities on college persistence

15:12-17:34 Helping students find career satisfaction; 70% of people “hate” their jobs

17:35-19:22 Multiple jobs in a lifetime; impacts of tech and AI

19:23-22:01 Helping students look at “what do I want my life to look like”

22:02-26:16 College and career exploration tools

26:17-29:14 Post-secondary supports

29:15-30:41 Key role of relationships

30:42-33:04 Ethical issues in assessment and hiring; navigating an automated hiring world; PD Fund for pay-ahead college funding grants

33:05-34:30 Outro

Transcript

Jon M: 00:10 Hi, I’m Jon Moscow.

Amy H-L: 00:17 And I’m Amy Halpern-Laff. Welcome to Ethical Schools.

Jon M: 00:19 Our guest today is Lindsey Dickson, Director of Career Readiness at the Urban Assembly in New York City. Lindsey is also the cofounder of the PD fund, a not-for-profit that uses a pay-it-forward model to help students finance their postsecondary education. Lindsay is currently a doctoral student at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign studying educational leadership and learning design with a focus on educational equity and socioeconomic mobility. She’s an Air Force veteran and a former Bronx high school teacher. Welcome, Lindsey.

Lindsey D: 00:54 Thank you so much for having me.

Amy H-L: 00:55 Lindsay, you’ve said that college and career readiness pathways operate on a very restricted model. What do you mean by that?

Lindsey D: 01:03 Well, I mean all the way through the pipeline of a young person’s experience and education, which then leads to the workforce, they are only exposed to certain avenues. And we talk a lot about college and career opening doors for people and being that engine for social and economic mobility. That can only really happen when people have doors to walk through and that really should imply multiple doors, right. So this was kind of the danger of the vocational education in America 1.0 was when we were really tracking people into you will be a plumber, you will work in HVAC, you will go to a four year degree, you will not, you will do the military. And I think that if we’re not careful now, we are somewhat in the danger of repeating that despite our best intentions because we’re only exposing young people to one thing. Right now, what’s in vogue is this, you know, college for all, especially a four year college for all idea. That has really limited our ability to help young people explore other avenues and then perhaps lead them into that four year degree later. But they are not usually given the same amount of information about amazing technical programs and technology training boot camps or the military or national service. There are many people who have found rewarding lives and careers after doing a year or two in AmeriCorps. And I just think we really should be not restricting our young people and our society into this one kind of homogenous pathway that we know really isn’t working in many ways for very many people.

Jon M: 02:29 So given that, what do you want the students that you work with to be thinking about as they start to look ahead?

Lindsey D: 02:39 I want our students to think about the future and their future and what they can build. I mean, I think the world right now is in a state of multiple different crises from climate to how we are treating animals, people, refugees, the value add of a college education and how much debt people are carrying. There are so many issues and problems in the world. And I want our students to be thinking about what their part could be in solving some of those things and preventing some of these things from happening in the future. And so I think education absolutely is the best tool to help them do that. But it has to be experiential. It just can’t come from a textbook. We’re not going to get back to the moon, let alone Mars, if we aren’t really thinking differently about, you know, 21st century education and we’re already in 2020 and I fear that we’re still going to be talking about 21st century skills in the 22nd century. And so I do think that exposing young people to technology and giving them an experiential education where they can go out into the world and solve big problems and understand that they do belong and they are the leaders that we’ve all been waiting for, I think that’s what the promise of education is and the promise of a real career pathways, which really tap into students’ interests and values and what they see as a need in their local communities and around the world and then just teaches them the skills to translate those problems that they see into ideas and solutions. And that’s what I do every day. And I feel very fortunate to do what I do with Urban Assembly.

Jon M: 04:11 So following up on what students should be thinking about and on this restricted model, you’ve talked about the fact that college completion rates are really low and yet a lot of students end up with a lot of debt, and you’ve argued that this wouldn’t really be acceptable in any other kinds of situation. Could you talk about this a little bit?

Lindsey D: 04:31 I think we have to take a hard look at the value proposition of higher education and compare that to other institutions that people invest time and money into. You know, if only about 20 or 30% of people saw any types of returns on the stock market, I don’t think people would invest. They wouldn’t spend the time and certainly the money if they weren’t going to see a payoff in the form of improved economic mobility, improved economic outcomes. Take housing, another important area of our lives and of society. If only 20 or 30% of people saw a return on their real estate investments, which you know, many people use as a form of a retirement fund, if only 20 or 30% of people were able to turn around and resell their home for a profit, I think everyone would rent, right? Because it just wouldn’t have the value. And so when we see higher education and we have those numbers sometimes in the twenties and thirties and only forties for positive outcomes for people who are actually getting that degree and earning those important credentials, especially when you’re talking about students of color, then I think yeah, we have a right to put that information in front of students and parents and families and help them make the best decision for themselves as far as, you know, investing in the right opportunity for them once they graduate high school. That could be an apprenticeship, that could be national service and all of those things and more can lead right back to college when young person has more experience and a better sense perhaps of what they want that college degree to do for their life and for their career. But I just think it’s important for us to back up, look at the data, look at what other other countries are doing and just ask some of those hard questions because there’s no question to me that higher education has a very, very central role to play in this. I also feel unequivocally that the current model is broken for far too many people and so we can’t just continue doing the same old thing over and over. It’s been many decades now that we’re seeing these results, and I just think they’re unacceptable and I think everyone has to take a look at what they’re doing, that’s K-12 schools, community based organizations and nonprofits, higher ed for sure, industry though, policy makers and government. We all have a part to play in this and I think we just need to be doing a better job of looking at the data. I’m looking at some of the research that’s out there about other models that are working and working for certain students and demographics and then roll up our sleeves and just get it done. One of the folks that I follow is Anthony Carnevale. He is one of the leaders at Georgetown’s Center for the Future of Education and the Workforce. And he was recently testifying in front of Congress for the Higher Education Act and he called higher education a risky business, right. He actually said that, that’s what he said. He said higher education is a risky business that has been risky for a long time now, and when 70% of people say their number one reason for going to college is a successful career, I just think that we have to be doing a better job of building those bridges. First of all, making sure they get into and through college, but then also into a successful career ladder job that’s gonna pay a family sustaining wage. When only one out of three Americans have a bachelor’s degree and only one out of four Black and Brown Americans have a bachelor’s degree by the age of 24, I think we just need to hit the pause button and ask first of all, is that what the end goal should be for every American? If it is, we’re way off the mark. If it’s not, then what do we all need to do to realign so that every young person has the best pathway and the best opportunity placed before them, and then they can choose which door to walk through that’s going to actually lead to success for themselves and for their families and for their community.

Amy H-L: 08:12 Lindsey, do you find the language of ethics useful in talking about college and career readiness, do we have an ethical obligation to ensure that students get the support they need to thrive in college?

Lindsey D: 08:26 Absolutely. I actually think ethics plays a huge role both on the education and the workforce side and then in the nexus between them in which counselors are such an important conduit, in that space. I think there are many opportunities that are not put in front of our young people and often by the best intentions, right. So what if you just have a college counselor who has perhaps no personal experience with the military or maybe does and it was negative. You know, maybe they don’t, out of the best intentions, put that option out there, but that removes choice and agency. So I do think, um, I do think there are ethical implications when we artificially narrow the range of options that young people could and should have to choose from. And again, be that national service. It could be, you know, taking a gap year. There’s so much pressure on high school seniors who are graduating in the United States to go immediately to college, whether or not they know what they want to do, whether or not they have a major even declared so those credits are going to be of worth to them, or whether or not their whole first year of college might be spent in remedial education. I happen to think that’s deeply unethical. If we’re sending a young person and we know their entire first year of college is going to be spent in remedial education, where they’re going to be sitting and if they pass, you know, not counting those credits for graduation and paying the same amount of money as everyone else. I just think there has to be a better way. What if there was a AmeriCorps program, for instance, or in New York City Civic Corps program that they could spend a year tutoring in a middle school and build their own academic skills, and then they could test out of remediation. They would have earned some money and they would have really important signals on their resume and a professional network by the age of 19. And then counsel that young person to go to college. So I do think, um, especially on the education side and the way that we counsel young people, and listen, this isn’t all on counselors because what supports are they given? What training are they given about the new world of work and the information economy? Do they even get training or support to know all the many careers that are out there for young people? I don’t think they do. Not adequately enough.

Amy H-L: 10:22 What responsibility, if any, does the school have to encourage students to think about their individual futures and how they might impact society’s wellbeing or the common good?

Lindsey D: 10:38 Well, I think you just summed up, in a nutshell, what I think the purpose of education at least at the K-12 level should be, and I don’t think this has been getting enough attention at the national level and even the state and city and district level. Um, one of the projects I’m most proud of at the Urban Assembly, at the middle and high school level, we’ve been working with the New York City Department of Education on a new grant called, you know, Middle School CTE: Exploring Futures. And it is all about how do we take a young person and help them design a pathway that really fits their life and will benefit society. So it’s not just this utilitarian go work, make money, usually some for yourself, but a lot more for someone else. How can we help you feel a sense of service? We have another school in our network called the Global Learning Collaborative that requires service learning, a lot of hours of service learning, for students before they graduate. So I do think there are vehicles and mechanisms for this and organizations like the Urban Assembly care very deeply about it. I do think it should be higher on the national radar because it’s just another way to experientially learn skills, connect to networks, and have a sense of purpose, which really is the most important thing to guide people in their career pathways and in life.

Jon M: 11:54 I wanted to go back a little bit because since you said it, it’s been running through my head as we’ve been talking. When you were talking about the college completion rates, could you break down a little bit, sort of where things are happening. So what’s happening in terms of the percentage of students who are graduating from high school and then once students get into college itself, whether it’s a community college, whether it’s CUNY, whether it’s a private school, what is actually happening in the colleges and, and to the extent that there’s a big drop-off there, why do you think that’s happening?

Lindsey D: 12:39 Well, I’ll say a few things. One, I focus a lot more on the career side of college and career. So I don’t have every single stat about, you know, the exact percentages. Some of my colleagues on our post-secondary access side of the world do have those more immediately at their fingertips. But we do know that the leaky pipeline starts really early and of every 100 9th graders, only, and I’ll take New York City as an example, only between 78 and 80% of those will graduate high school. So now that’s your new bucket of students and only around 50 something percent of your original 100 are going to go onto college. And then the persistence rate drops drastically after the first year of college. And there’s a phenomenon called “summer melt” that we have a program at the Urban Assembly called Bridge to College to help. So summer melt is when a high school senior gets accepted to a college, graduates from high school and probably has every intention of going to college. And there are a range of reasons why first generation and non first-generation future college students don’t actually make it, from finishing up their paperwork, not understanding what a bursar is. I don’t even know if I understand what a bursar is, um, just not having that kind of familiarity. So we have coaches that actually spend the entire summer near peer model of recent college grads to help coach through. And even then, not every single student makes it through, but our numbers are certainly far better than the average. And then in the first year, we see a lot of students struggling just to acclimate to the different environment. High school academics and college academics are very different, not just in rigor but in style. And that can be a really hard shift for students if it’s the first time they’re encountering an environment like that. But most of the research shows that the number one reason that students are going to drop out, or the number one and number two, is around family responsibilities and economic need. So if they are raising a family, helping raise siblings or just housing insecure, food insecure, which very many CUNY in New York City college students are, that that becomes such a barrier that they are not able to persist. And one of the other top two or three reasons is poor fit. So maybe they thought they wanted to be an engineer, but nobody really ever gave them a chance to explore that. They never completed an internship and they go off to do this work and they realize, hey, I’m taking this time that I’m not working full time and earning a wage and spending all this money and I actually don’t like this thing. And this is probably the first moment in their life where they actually got to decide for themselves, oh, this is not what I thought it was. So that really comes up fairly often as well. But I do think the top reason is economics.

Amy H-L: 15:12 Lindsey, taking off on that idea of poor fit, I’ve been reading some pretty horrendous statistics lately about millennials who are dissatisfied or actually hate their jobs. How do we prevent some of that? Is there some sort of introspection that students should be doing before they launch their careers?

Lindsey D: 15:34 I think it’s a great question. It’s one of the things that has kept me up at night but kept me motivated for the last several years. I also read a survey recently that about 70% of us hate our jobs and I mean hate, like they use the word hate or low or deeply dissatisfied with. And when I talk to people about this, I say, you know, that affects all of us. If you’re in the 30% like me, who is very lucky to have their dream job or feel at least moderately happy and fulfilled at work, like that’s awesome for you and we want to grow that number, but you’re still affected by angry crossing guards that aren’t paying attention to traffic and disgruntled dentists who, well, you can fill in the blank there. And so I do think this is something we have to pay attention to. And I do think part of the problem comes again from this kind of focus on just purely academics and test preparation in middle and high schools. A high school senior in America, certainly New York State, can graduate literally without ever having spoken a word. They do not have to know themselves. They do not have to know, say, can you list your top five skills Jorge or Annabella, can you tell me three of your values or Steven, how will you contribute to your family and society? They don’t have to answer that question. They have to answer, you know, what was the migrational pattern of the Bantu tribe in the 1700s or you know, some other really content-based thing that most of us can Google or our students are just going to ask their smartwatches. So I do think assessment drives a lot of instruction and there’s a very broken part of what and how we are still assessing young people who, you know, between the hours of eight and four are kind of legally locked into these seats where usually they can’t have their phones out and it’s all about memorize this stuff that someone decided was important. And then they go home and then their interest resurges, they’re on their phones, they are mediating conversations socially. But that’s not what they get from the eight to four so I do think K-12 has a lot of this burden to bear and really needs to be very innovative if we’re going to change this really big phenomenon of people just hating their life, their nine to five, which is what we do most of the time when we’re not asleep.

Jon M: 17:35 Speaking of that, these days, most people will have multiple jobs or may find their jobs eliminated by technology and artificial intelligence. How does that impact the advice you give students?

Lindsey D: 17:47 Well, we tell them that this is probably more urgent for them than any other, at least living generation. Certainly the probably second industrial revolution and the third, you know, have some horror stories that they could share if they were still around. But our young people are growing up in the fourth industrial revolution, and at the Urban Assembly, we tell them that and we tell them what that means to grow up in a completely technology mediated society and that it means, yes, you may work two or three jobs. We talk to them about the gig economy. When I was going through high school, that was not a word, let alone something that anyone taught me, but we tell our students about how to determine if you want to create your own product or service, how to market yourself and digitally brand yourself if that’s something you want to decide to do. One of our schools, the Urban Assembly Gateway School for Technology in Midtown Manhattan actually help students start businesses while they’re still in high school. They can start their own clothing lines, and some of them have, or they can start their own technology support companies and and be consultants while they are still high schoolers, and I do think that more and more, already something like 40% of that age range, are already involved in the gig economy. So we know that is going to increase, but also just we have to get people to have a different mindset and a mental schema for what a career is. It is no longer 40 years as a clerk or a teller or even a doctor necessarily. We’re going to all have to get very flexible with our idea of career and we’re teaching our students how to do that by thinking about skills and not job titles, right, transferable skills that you can layer on and stack and credentials that will follow you for the rest of your life. So it really is not a buzzword. Lifelong learning is everything.

Amy H-L: 19:23 So Lindsey, do you think that there is a role of counselors and institutions to help students look at what a full, rich life might look like to them? Not just a career, but also hobbies, perhaps avocations?

Lindsey D: 19:42 Yes, absolutely. Yes. And I think this is where we need to think about how to scale something like that type of intervention and use technology really smartly. But there are platforms out there that colleges, counselors and guidance counselors could use or even just paper-based methods that really do help young people determine how to develop hobbies, skills, interests. I really do think that is so much of the core of how we determine our identity around career. Because there are really, really strong ties, not just in the United States but around the world, between what we do and who we are. But I think that who we are part has to come first and that it’s somebody’s job to help them explore that. So certainly it’s not all on the shoulders of counselors. I do think we should be spending more time in our classrooms writing about and researching about and digitally sharing these types of things with one another to help create mental models of what is even possible. Like, oh, I’m a young girl. I didn’t even know I could be an astrophysicist. Like that wasn’t even a thing I thought I could be until I saw it. So I do think it is the role of counselors and I do think that this should be much more on the radar of high school requirements than a particular test score, which most employers no longer or never did find relevant. And many colleges are even dropping some of the requirements for these national test scores. But what they do need is to have a really strong sense of self and the social emotional skills like social awareness and self-awareness are going to be what allows them to succeed, whatever pathway they choose. But again, most schools are not spending any time on that. So I do think counselors should have some method, ideally using technology or at least some type of system of making sure every single kid gets to sit down and determine, again, not as you said, not just careers, but what do I want my life to look like? What type of home do I even want to live in? Do I want to have a huge, huge mansion or do I love tiny homes, which I personally do. So I think those should be on more people’s radars and they’re very environmentally conscious. You know, do I want pets? Do I want to have children. And maybe I don’t know that. Do I want to adopt? Do I want to travel? Have I ever traveled? If I haven’t, maybe I can’t even make the decision yet. So let me take a virtual reality tour of another country using Google Cardboard, which is like $10, so I just think all of these experiential things going back to even like the best of our philosophers from Dewey and Vygotsky and Bandura, they’ve been telling us this for hundreds of years. I just think it’s time we listen.

Jon M: 22:02 So what are some of the tools that counselors could be using for some of this? What have you found particularly useful, and are there cautions with any of them, you know, in terms of whether they’re being used in the best possible way or whether they in some cases can end up tracking kids in ways that you don’t want them to? What do you recommend or what do you think people should check out to see if they work for them?

Lindsey D: 22:25 Absolutely. There are some that are pretty high on my radar. Part of my doctoral program recently, I had to do a bit of a competitive analysis from about seven different college and career exploration tools, one that we’re piloting in two schools, the Urban Assembly Unison School in Brooklyn and the Urban Assembly School for Criminal Justice, also in Brooklyn, which is an all girls high school. So we’re doing a middle school and high school pilot. That platform is called Xello, X-E-L-L-O. We’re really liking the results we see so far because, as I was saying before, it starts with, you know, how do you think you learn best? What are some of the things that make up your personality and how are you uniquely individual? What are your interests? What careers, you know, that you’ve ever even heard of are you interested in exploring more? So it is a very personalized learning kind of competency- and knowledge-building platform. And we’re seeing really strong results with students. Maybe saying, oh, I wasn’t considering college before this, but now that I got to explore it, including like a map and understood how cool college is and how different it is from high school. And we got to read these day in a life and watch these videos that they’re really having just a much bigger idea of who they could be in the future. So we’re going to, you know, stand by for more results, which we’ll post on our website, but we are really finding that this is a promising tool and it’s one that the Department of Education has supported us with a grant to deploy and potentially it’ll roll out to more schools in the future. I guess that’ll be based on the results.

Amy H-L: 23:53 That’s fantastic. I wish that these types of tools had existed when I was a kid.

Lindsey D: 23:59 Me too.

Jon M: 24:02 Are there others that you either think would be useful for people to check out? Because our audience is in something like 45 states and 40 other countries, so people are going to be in a wide variety of circumstances. And then if there are any that you think could be good, but that you’d also have cautions about.

Lindsey D: 24:20 Absolutely. So there are some our other schools are using. There’s a platform called Thrively that our school CompSci High or Urban Assembly Computer Science High School is testing. So that’s like the word thrive, Thrively, and it has a lot of overlap with Xello. There’s another, You Science, so Y-O-U science that I think some of our schools and other schools in New York and around the country are considering. We found a lot of things to love about You Science. We want to understand the research a bit better on their work into aptitude. Because your question further, and this is not a knock on You Science, but just in general, one of the caveats or the cautions that we have is like to narrowly telling a student this is what you’re good at and this is what you are not good at, so you should just only consider things in this bucket if things you are good at. Because we know that learning is this lifelong process and it is not linear and it is not an absolute thing. It is a relative concept. So I would be cautious about, you know, too narrowly telling a young person, well you have like a great degree of, you know, visual spatial acuity so you should be, you know, this type of engineer when really maybe they just want to be a dancer or a poet and maybe they have multi skills, right. So I think that one is one to look at for sure if you’re in an international audience, but one to look into some more of the research behind aptitude versus interest. I think there’s strong research around a theory called career decision-making self-efficacy, and that builds on the work of social, cognitive career theory. And even back to the Holland codes and the Holland codes told you, you know, are you realistic or imaginative, are you more social or are you more enterprising and conventional. That theory is still grounding a lot of this work and you know, has had good results with helping people find careers, but it’s much more around interest, personality type learning style. So I think those, the ones that really do that and to our conversation earlier, help a young person just explore more about who they are, not what they are or what skill they are, are the ones that we find more promising.

Amy H-L: 26:17 So these sound like fantastic tools for students considering what their next step is. Once they graduate, what types of supports should we as a society or specifically the school be providing to help students as they move into the next phase of their lives and their careers?

Lindsey D: 26:39 I’m so glad you asked that because this has been a topic that has been deeply on our minds at the Urban Assembly and I know many of our partner organizations and at the Department of Ed in New York City, which is the biggest school district in the country. So sometimes as goes New York City, so goes other districts. And in this way, I hope so because we’ve really been focusing on supporting our alumni and we have a new alumni success team that is led by, you know, a phenomenal, a practitioner with a background in workforce development. And we’ve been building on the work that our amazing college team has already been doing with technology-based intervention. So there’s a lot of, you know, kind of behaviorist theories and science around, you know, the benefit of nudging and just sometimes it’s just a reminder for a young person whose frontal lobe is not finished quite cooking or building or you know, getting all those neurons in place, not by 18 and still not by 21, so sometimes it’s something as simple as sending them a reminder that their FAFSA is due or sometimes it’s sharing a resource, maybe you don’t in your iny our immediate family or, or small circle of community have somebody that could help you, say like, hey, here’s a really great resume template for a recent high school grad or here’s a video to help you build a LinkedIn profile because everything is about who you know. We still get 70 to 80% of the jobs in America by who we know or someone who can open an employment door for us. So here’s this really, you know, phenomenal global tool, but they don’t teach you this in high school. My team does. I’m very proud of my team, the career readiness team, for doing this work in schools. But by and large, most high school students graduate and leave without that strong resume, that LinkedIn and even just some of the skills that I think that we could help them with if we were connected and supported and they felt like they could reach out back out to us. So now we are really leaning hard on not just K-12 but alumni support at the Urban Assembly. So it’s definitely going to be an area to watch.

Jon M: 28:22 And that alumni support includes the students who are going on to college. Do they tend to stay in touch with you?

Lindsey D: 28:27 Absolutely. Both sides of the house stay in touch with us, which we’re really proud of. So most of our students do go on to college right after high school or shortly thereafter. But there’s also many of our students for a variety of reasons that choose not to and they stay in contact with us as well. So we send out surveys to try to figure out what are the barriers for them, whether it’s in college or to find a job. They reach back out and text us through our texting platform to say, hey, I’m looking for a job, or could you give me feedback on this resume and a variety of things, or just like, I’m a little stuck right now, or I’m hungry. I mean sometimes it’s just the basic human needs and they need a place to reach out to and we are not necessarily the ones to feed them. Occasionally we can provide economic support for our alums, but we can connect them to the rich services that the city provides that just this young person may not know how to tap into.

Amy H-L: 29:15 Yeah, that speaks to something that we always emphasize, which is that it’s all about the relationships and if your alumni feel comfortable contacting you, I think that’s, that’s key.

Lindsey D: 29:27 Totally agree. And that’s why the newest program we’ve launched at the Urban Assembly is called the Urban Assembly Career Peer Student Leadership Program. So we’re actually paying high school seniors across every single school that we work with, across, you know, 11,000 students just in New York City. We’re paying at least one or more of them per school to be that kind of peer leader for each other and to create community and to create those tighter bonds that will last after they leave. So we train them how to do resume review for their peers, how to create LinkedIn profiles. Several of them, because this is National Career Month in February, several of them today and tomorrow are leading mock interviews with their peers. Because that’s a terrifying thing. I don’t know if you guys remember your first interview, but sitting down and sweaty palms and you don’t know these people who are older than you and more experienced and maybe this is your first job. That’s just like a very nerve wracking thing to throw a young person into without practice. And so these young people can help each other practice, sometimes a lot better than us old folks can, and they will listen to them and really, you know, create those relationships that we’re hoping will last many years after they leave high school and then they can reach out five years down the road. Not just for a job but maybe a recommendation because they need to go back to grad school. There’s all kinds of ways that we can help one another if we stay, you know, more tightly linked in community and through relationships.

Jon M: 30:42 Is there anything else that you’d like to add that we haven’t talked about?

Lindsey D: 30:46 Just I’m really glad that podcasts and work like yours exists. I do think there are so many ethical implications for the future of work, especially when it comes to, I’m actually writing a paper on artificial intelligence and assessment right now and of course as it intersects with college and high school, but especially with hiring, There’s so many assessments now for hiring. Even the, not just the ones that, you know, everyone is a little bit more familiar with like algorithms that sort based on, you know, more traditional Anglo Saxon names and maybe they are weeding out based on, you know, ethnic bias. But now they have ones that are looking at you on a video and assessing, you know, do they smile and they’re giving you an empathy rating on, you know, do you show concern when someone else, you know, is experiencing some type of hardship in front of you. And these are like, again, artificial measures of someone’s input of this is what it means to be empathetic, this is what it means to be curious. And so I think there’s a lot of potential here if we could get it right to screen out bias. But right now I’m deeply concerned about this area and it’s something that’s just ramping up more and more as everything becomes automated, as we automate tasks, especially, and there’s so many, you know, factories now and Amazon and other companies that are entirely entirely mediated by robots, algorithms and machines. How can we help our young people prepare for that world, not just on the skills base, but to navigate, you know, a system where it may not even be a person answering the phone or looking at your resume? So I think there’s a lot of like ethics work that needs to be done there. And I know that work’s already happening, but that is something that I’m thinking about very deeply. And then I guess I would just say in in conclusion that this very small nonprofit that I launched called the PD fund, we are about to launch another round of funding students. So if you’re a student listening and you want to go back and get your education, but maybe you’re a single parent and you can’t afford childcare or you are a student who got scholarship for tuition but they didn’t give you enough to cover your housing, look us up at pdfund.org, and we’re building a small but growing community of people that want to get their education. Maybe it’s a tech bootcamp, but then once they earn their education and then go on to get a great job, they want to pay back into this community so that more people can benefit. So I’m really excited about it and we’re going to open a another wave of funding in the next month.

Jon M: 33:05 Thank you so much, Lindsay Dixon of Urban Assembly.

Amy H-L: 33:08 And thank you listeners for joining us. Check out our website for more episodes and articles. We’ve begun to post annotated transcripts of our interviews. We offer professional development on social emotional learning, with a focus on ethics, in the New York City area. Contact us at hosts@tethicalschools.org to talk about your school or youth program. We’re on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter @ethicalschools. Our editor and social media manager is Amanda Denti. Till next week.

Credits

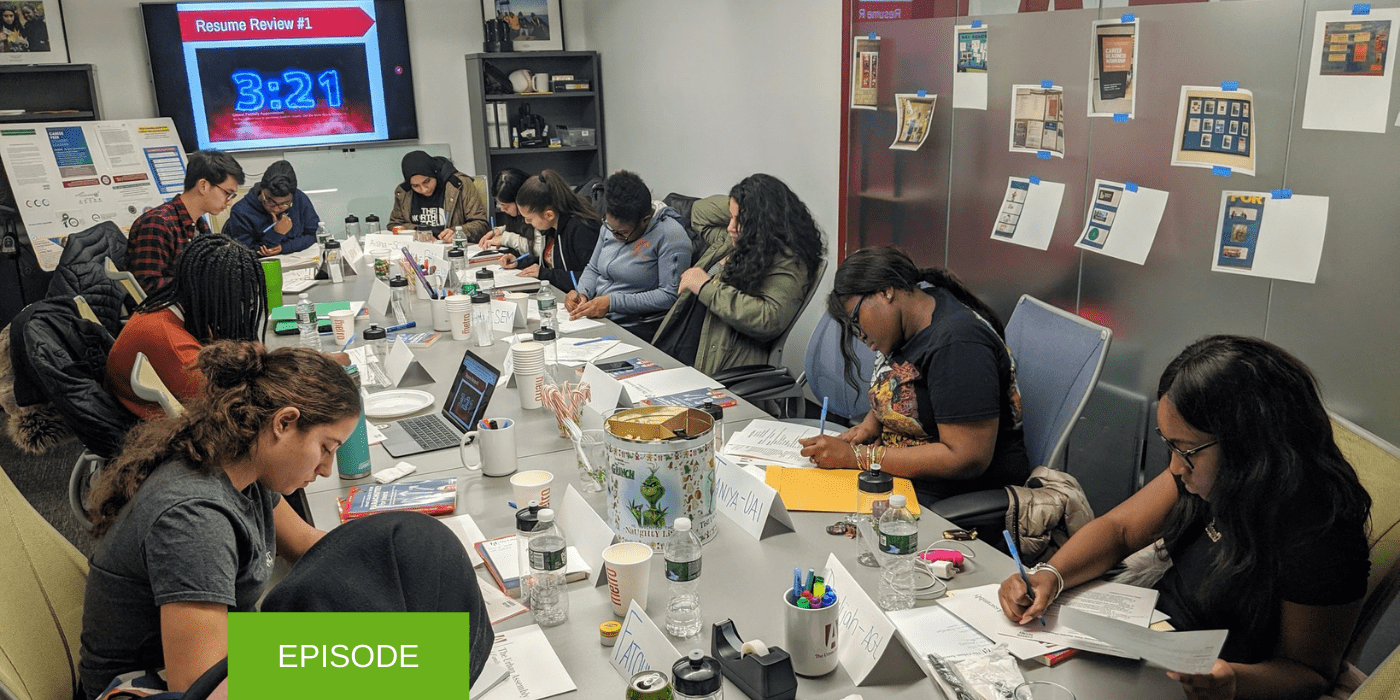

Photo: twitter.com/urbanassembly

Soundtrack by Podington Bear