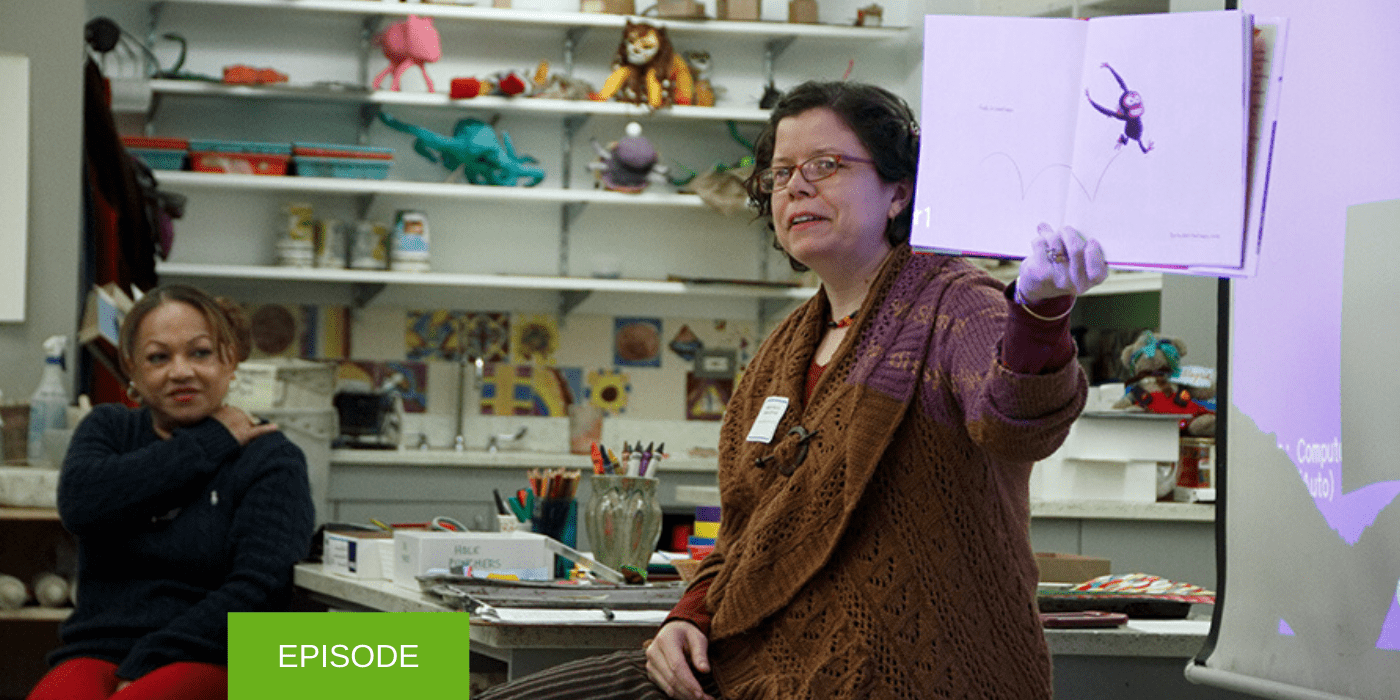

Margaret Blachly of Bank Street’s Center for Emotionally Responsive Practice describes how to fit materials, curriculum, and relationships together to create an emotionally safe classroom. Emphasizing the importance of a deep understanding of child development, she tells how important it is to know each child’s “story.” Margaret shares what she’s learned as a dual-language and special ed teacher and gives advice to new kindergarten teachers. Reflecting on Dewey’s Education and Experience, she talks about the ethical dimensions of teaching and the connections between the classroom and the larger society.

*Overview and transcript below.

References

- During the interview, Margaret refers to the book “Creating Schools that Heal: Real-Life Solutions” by Lesley Koplow. You can find it here.

- Margaret also co-wrote an article with Noelle Dean for EIEN titled “Feeling charts instead of behavior charts: radical love instead of shame”. Click here to read it.

- To know more about Bank Street’s Center for Emotionally Responsive Practice, click here.

Overview

0:00-1:46 Introduction

1:46-5:02 Center for Emotionally Responsive Practice; importance of deep understanding of child development

how each child’s life experience affects who they are, act, think, connect

5:03-11:59 Components of emotionally responsive classroom; “inviting and “containing”

11:59-16:06 Influence of John Dewey

16:06-22:00 “Aha” moments; growth and change in teachers

22:00-35:33 Immigrant experience; using reflective techniques; loss; inviting stories in that are hard

35:33-39:46 Changing school culture; teachers bringing their whole lives into the classroom; reflecting on their

experiences; feeling valued

39:46-48:33 Dual language, translanguaging; Ofelia Garcia

48:33-54:09 Advice for beginning kindergarten teachers

54:09-1:01:35 Connections between special education, bilingual education, and dual-language education;

decentralizing white experience as the first or only experience

Transcription of the episode

Amy H-L: 00:00:15 I’m Amy Halpern-Laff.

Jon M: 00:00:18 And I’m Jon Moscow.

Amy H-L: 00:00:18 Welcome to ethical schools where we discuss strategies for creating inclusive equitable schools and youth programs that help students to develop both commitment and capacity to building ethical institutions.

Jon M: 00:00:34 Our guest today is Margaret Blachly. Margaret is a psycho-educational specialist at the Center for Emotionally Responsive Practice at Bank Street College. She’s also an advisor and instructor in the early childhood special education and bilingual programs at the Bank Street Graduate School of Education and a learning specialist at the children’s learning center of Morningside Heights. She has been a teacher for two decades. Welcome Margaret.

Margaret B: 00:00:57 Thank you.

Amy H-L: 00:00:59 Margaret, how would you define the term psycho-educational?

Margaret B: 00:01:03 That is a wonderful question and it’s funny you ask because when I first saw my contract for taking on the job at emotionally responsive practice, I said, “Is that what I am?” And my, my director Leslie Koplow said, well, that is what you are. So I had to do a little thinking about it. Um, psycho-educational specialist to me means somebody who knows about and thinks about and can advise and teach about the impact of emotional health and wellbeing in the educational setting.

Amy H-L: 00:01:40 And what is Bank Street Center for Emotionally Responsive Practice? What does it do?

Margaret B: 00:01:46 So the Center for Emotionally Responsive Practice is 20 years old and it’s a professional development branch of Bank Street College. It’s a staff at this moment of six people with our director and founder, Leslie Koplow, and we work with teachers, we work with administrators and we sometimes also work with children. We work with paraprofessionals and we sometimes also work with parents. We work with individual schools. We sometimes work with districts and we come to the schools or they come to us to learn about children’s emotional health and how it impacts their learning and their behavior in schools. We do seminars and we do coaching. We do support groups and we do parent support groups and parent workshops. We have an annual conference and each of these events or each of these different ways in which we work, operates on a similar premise that people who are in contact with children in an educational setting need to understand child development and they need to not only understand the development of the age of the children that they work with. They need to understand child development starting with birth and they need to especially understand child development over the first three years, four years and five years of life. We also operate on the premise that people that work with children and families need to honor and value that each child has a story and that that child’s story, aka their life experience, affects who they are and how they act and how they think and how they connect and that sometimes their story impacts how school feels for them. In fact, it always does. So whenever, whenever grownups come to us saying, we’re having so much trouble with child X, can you help us? The first thing we say is how old is child X? And tell us about who they are. And then the other is what do you know about this child’s story? Let’s make this child more of a whole human then, uh, this behavior that you’re seeing in your classrooms setting. And it’s usually through beginning of the conversation that way that we are able to offer a space for the grownups to consider that child in a fuller way and thus to find a way to respond to them in a fuller way and in a way that’s more that, that values them more, that honors why they’re doing what they’re doing and who these grownups are. Who is this teacher to this child? Who is this principal and who do they want to be? So we think a lot about development, a lot about experience and a lot about relationship.

Jon M: 00:05:03 So building on that, can you give some examples of what emotionally responsive practice looks like in the classroom?

Margaret B: 00:05:12 Okay. There’s some very basic components to an emotionally responsive classroom. However, it can look different from classroom to classroom. So I want to, I want to lay that premise out from the beginning that with the same idea in mind, two classrooms can look and sound pretty different but the effect can be the same, that children feel safe, secure, known, and able to engage. So one example is having a space like a cozy corner. Some classroom teachers call it a peace corner, some teachers call it a peace nook. But here’s the physical environment that says sometimes living in a group feels like too much. Sometimes a child, sometimes a person. Needs to retreat. Sometimes a person needs to regroup and have some space to be on the edge looking in and get ready to rejoin. So the presence of a peace corner or a cozy corner and then the way that it’s used is one really clear component of an emotionally responsive classroom. We talk about a framework of inviting and containing. And this has been very helpful to me to think about and it’s one of the things that we challenge ourselves to explain to teachers and to get them to be thinking about. So inviting and containing. is a balance that a classroom that it teacher wants to create an a classroom and I think that a school leader wants to create an a school that a coach wants to create in a coaching session that a graduate instructor wants to create in the graduate classroom. There needs to be invitation for who’s in the room to be welcomed and heard in the room. There need to be structures that contain the activity and the way things work within the classroom. So a classroom that’s overly inviting can feel really chaotic and I’m the first to say that my very first kindergarten classroom was overly inviting and it wasn’t containing enough and I needed a Bank Street advisor to tell me that actually many years ago. When she told me, you can’t open so many areas for your project time at once, I was very resistant and I said project time is the most important time in my classroom.This is when these children are going to get to engage with materials on their own terms. This is what I come from in Bank Street pedagogy. This is experience. So learning, if I don’t open blocks today, that’s one day less that the children in this room will have to play with blocks and their life because I knew that they wouldn’t have blocks first grade. and this was really it. I felt the stakes were really high, but my advisor said it’s too chaotic. You’re not able to. um, you know, the kids are throwing blocks, they’re throwing sand and over on the other corner they’re throwing baby dolls. And it took me a while to, to admit that she was right and scale back and look at the goal of having all of these open for children, but realizing that I needed to be more containing and more structured in the way that I open them one by one, set out clear expectations and shared knowledge of how the things were going to be used and got the room full of kids, used to working in a lot, a lot of different centers at once. So I think that that’s one of my personal stories of inviting and containing before I even knew these terms. I’ll share another from my own personal experience because this is one that I often share with teachers who I’m supporting, and it’s interesting because it just came up recently with a parent who I ran into who was telling me about a classroom where the teacher just wasn’t progressive and made the kids sit in assigned seats when they were having meetings together and I, I thought about it and decided to just tell her that personally I have come to really value assigned seats, particularly for new teachers. And this was another thing that happened for me early on in my career where I felt very tied to value of choice and I really wanted children to be able to choose seats that they knew were going to be good for them, where they want it to be. I wanted to honor them. I didn’t want to tell them where I thought they had to be, but I found that every time we came to the carpet together to have a conversation, there was so much anxiety about where kids sat. There was so much arguing, there was so much getting in each other’s spaces that when I made the hard decision to give them assigned seats, it actually really relieved that anxiety and allowed our conversations to go on. And so it’s an example that I don’t think, you know, I’m not saying every single teacher must assign seats because there are teachers who have really figured out how to make, not having assigned seats work, but for teachers who are having a tough time managing that, I say assign the seats, relieve the anxiety so that you can get to the content of the conversations you want to have, the community that you want to create. And it’s a way of saying to kids, there’s a space for you. You can depend on it. You don’t need to worry. You don’t need to wonder. You don’t need to think my friend’s not near me, does she like me anymore. You can kind of relax into that space. And the funny thing is I’ve found that when I teach grownups, once they’ve figured out their seat, they always come back to the same seat in the graduate classroom or in the ERP [emotionally responsive practice] seminars and it’s very comfortable to feel like you’ve got a spot, you belong there and you can join the group. So there are a couple of real life examples of inviting and containing.

Amy H-L: 00:11:59 Thank you. As you know, our podcasts and blog are strongly influenced by John Dewey’s approach to ethics in education. Do you see connections between Dewey’s ethical framework and the work that you do?

Margaret B: 00:12:13 So I think a lot about Dewey. When I did teach the courses at bank street in early childhood curriculum, Dewey’s experience in education, which is one of his later works in which he reconsiders and re States many of the things he said in his other books about pedagogy and the educational approach was one of the main texts that we needed to ask graduate students to read and think about and apply to their work. I’m not currently teaching these courses in the graduate school. But for me, going back to that Dewey text, which I had read long ago in the same course myself many years ago, was extremely helpful to think about the experiences that we offer children and to honor the fact that for every child coming into our spaces is part of their experience and is itself an experience. So we make choices as educators about the kinds of experiences children can have and as an extension, the kind of experiences their parents can have, their families can have. Um, I think about engaging with materials and Bank Street’s developmental interaction approach, uh, which asks educators to think about the materials, the curriculum, and then also the relationships that are in the room. All of these things fit together more and more. The more I repeat my reading of them and Dewey to me says that the educational experience can be and should be a parallel to the larger social experience and the very hopeful view that experiencing democracy in a classroom setting in a school setting prepares kids to grow up and engage in a democracy. In the very idealistic view of what a democracy can be, a social and political construct where people have voice, where people consider others, where people have choice and where they also have responsibility. Then in terms of thinking about the ethical framework, I understand this as the macro level of what our teaching means, and perhaps this is just another way of saying what I just said before, but our, our work as teachers and educators exist within a much bigger framework, a social, a political framework. And when we take the time to consistently reflect on ourselves at the macro level, thinking, what does my work with these children mean as a part of a larger institution of education in this country? And then on a micro level, what does my relationship and my, my educational offering to these particular children and these families this year, this day, this month, how to use my creation of a learning space that honors and welcomes and esteems children and their families and considers a developmental moment and how does it affect them personally? So I think there’s an ethical responsibility to see our role in kids’ experience and in their development of self within our spaces.

Jon M: 00:16:06 So Dewey of course talks a lot about change and how people make decisions and dramatic rehearsals is his phrase. And you were talking about how you changed in your practice, how you grew as you saw that some things seem to work better than others. And you of course were also coming out of, for example, a Bank Street background where you, you came to teaching from this. Um, what’s the change process that you see as you’re working with teachers who may not have come out of these backgrounds as they move towards sort of a more emotionally responsive practice? Do teachers, and I’m sure it’s different for every teacher, but do teachers describe aha moments? What are sort of getting at is we have so many traditional schools, you know, for all the people who study him in graduate schools, Dewey was never the dominant impact on American schools. It was always much more hierarchical and top down and so forth. And as you’re working with teachers in classrooms and also in schools that may not be progressive as such, um, how do you see this process of change and how do you see lasting change taking place? I don’t know if that’s, that may be a whole bunch of questions all bundled into one, but take whichever pieces of it you like.

Margaret B: 00:17:34 Okay. Yes, that’s a bunch of questions. Um, the first thing that came to my mind as you started to ask that question or those questions was it’s not always an aha moment and that has been something that I’ve needed to make peace with and that my colleagues at ERP whose training is in social work rather than pedagogy have really helped me to understand the process of growth and change over time in relationship with people. So I actually, I could tell you a couple of stories with aha moments in them and I’ve got one in mind and I can also tell you some stories of change over time. And I think both of them offer something for teachers to think about and maybe self-reflect, whether you’re thinking about your own practice or thinking about how to support other people who you would like to see grow. So there was an aha moment that happened several years ago when I was working at a school way out on the edge of Queens near the ocean. And our work at that time was responding to hurricane Sandy. And we had in that work more than we usually have. We had a curriculum planned out where we would come in and actually offer some lessons to the children and teachers and some invitations to share and express their stories. And one of the stories was about feeling scared in a storm. One of the books that we read was about a bear that feels scared in a storm and how this bear and their friends figure out feeling safe. And the thinking behind this lesson was that children needed to have an invitation to talk about the hurricane being a scary experience being a storm that was very scary. And then thinking about how they stayed safe or how they could stay safe in the future. Not on the practical level, not on making an emergency plan or anything, but really on the idea that after a scary moment there can be safety. And it’s important to know both of those feelings that hopefully the classroom can be that safe place. Now that was the idea. The story had these pictures of a dark woods in the night with rain and the minute I opened this book, now this was in a classroom with a lot of children who, who were themselves recent immigrants into the country or were the children of recent immigrants into the country. And interestingly, this work post hurricane Sandy was actually maybe a year and a half after the storm because of the amount of time that it took for funding to come to come through. So that our proposal for supporting these schools post-Sandy happened a year and a half later. However, it felt very impactful because a year and a half later people who had experienced the storm still were processing and still really responded to the opportunity to process together, to make sense of and to find comfort. However, some of these children were not even in this country when the storm happened, but here we were bringing this curriculum. And the minute I opened this story book, a six year old boy looked at it and spoke in Spanish, and I speak Spanish because of my year abroad during college and because it was something that I really wanted to learn to do and I became a dual language and bilingual educator. So I felt very fortunate to be understanding of what the child was saying because what he said to nobody in particular was that dark woods looks like when I was coming here with my mom and we had to hide in the dark scary woods and I was really scared.

Jon M: 00:21:59 Wow.

Margaret B: 00:22:00 And all of a sudden his teacher looked at me with this sort of aghast and shocked look on her face. Um, the teacher herself was an immigrant from a central American country and was a very experienced educator, but she had been worried about working with this boy who had been running out of the classroom. And when the school security guards approached him, he screamed and ran further. And so she had just been asking me what I thought about this boy and then he offered this, um, quite amazing statement in the middle of this story. And, uh, we got to write about this story in an article that I co-authored with two of my ERP colleagues, uh, because it was, um, it was sort of like an ERP moment that, so you can, you can read that story if you’re interested to hear more about our thinking about work with kids for whom an immigration story is part of their own experience. But the reason I’m bringing it up right now was really about what happened when the teacher looked at me and when I said to her, after I read this book, I’d like to work with him. And so I used emotionally responsive practice technique of being reflective and simply said to the boy in Spanish, that sounds like a scary story. Maybe after I read this book, you can tell me more about it if you want. And the reflective technique is offering a mirror to the child. I heard what you just said. It sounds scary and you can, you know, it’s, it’s invited here. So I read the story to the class and I set them off on their writing and drawing activity. And I said to this little boy, would you like to tell me more about your, about your story of coming here with your mom? And another little boy joined in and, and I actually felt a little overwhelmed by having both of them, but the teacher looked at me and said, well, he, he just arrived here, too. And we, I ended up having this conversation in which the two boys told their stories and the teacher listened. And then they both drew pictures about their stories and the teacher listened. And she said to me, as I was getting ready to leave the classroom, I had no idea that they had an experience like that. And she was visibly moved, shocked. Um, and really clearly thinking about this. Well, when I came back two weeks later, she said, after hearing that story, I decided to make a curriculum about our heritage countries. So all of the kids have made little presentations and little diorama’s and little posters about their heritage countries. And it was quite lovely and it was, you know, you might even say it was traditional, but the place it had come from was this teacher realizing the need for these children’s stories and experiences to be part of what was happening in her classroom. And the fact that she heard the child tell his story changed the way that she acted with him. She became more nurturing and more comforting and that helped him not feel the need to run out of the classroom. So there’s a story of an aha moment. Um, then there’s a story of a teacher who used her relationship with the ERP coach to help herself grow and to push herself to offer something to the kids in her class. This is a story that took place at a school out of state where we’ve been working for several years and this was a fourth grade teacher and it was only her second year as a teacher. Um, she was young and she was a white teacher and most of the kids in her class were not white children. They were African American, African immigrants, Latino, Latina, Latinx, um, how they define themselves. And she was really grappling, I think, with how she could offer these children a space to share their stories. She was not yet saying things like, I’m a white teacher teaching kids who aren’t white yet. She was clearly trying to think about it. She had read some books over the summer that she was considering reading to her class and one of them she felt like was maybe a little too old for them, a little too scary. And it was the book Ghost Boys by Jewel Rhodes, Jewel Parker Rhodes. And I was not familiar with this book. It is quite an amazing book in which that that addresses police shooting of unarmed black boys and brings Emmett Till in as a character from beyond the grave. And she couldn’t decide whether to read this book to her class or not. But she listened to them and the kids told her some stories that made her think this might be a good book to read. And she decided to take a risk and read this book. And the risk was really that the material was going to be too sophisticated or too complicated for her to explain to the kids or for them to process. There was a lot of loss in this particular group. And when she started reading the story, some of the kids’ experiences of loss came up. And it was loss across the spectrum of loss, – death, separation, immigration stories, moving and some, some tragedy. There was somebody who had experienced a shooting in their family. And so she decided to read this book and then she wrote to me saying, I started reading this book and everybody started crying and I don’t know what to do. Can you help me? And so I consulted with Leslie, my director, and we talked about how inviting hard stories into the room, it can be scary and can be overwhelming, but giving them a place to live can be therapeutic, can be comforting. And so I told the teacher that when I came back we would do an activity.

Jon M: 00:29:15 When you say giving them a place to live, could you elaborate what you mean by that sentence?

Margaret B: 00:29:20 Yeah, I think my story will give the example,

Jon M: 00:29:25 Go ahead.

Margaret B: 00:29:25 So, um, we thought, what if the kids make, what if we give them an invitation to make a page of a class book where they can tell the story of somebody that they’re missing and we’re going to keep it open ended because we don’t want to pressure anybody to tell a story they’re not ready to tell. But we want to open the space for kids who want to tell whatever story they want to tell. And so I did bring that invitation and I said, I heard from your teacher that you started reading this book, Ghost Boys, and that some of you started thinking about people that you miss and that it was sad and it can feel really sad to miss people. And so today I’m going to invite you, if you want to make a picture or write a letter or write a story about a person you’re missing, we’re going to put them all together in a class book. And so it turned out that this group of kids was very, very responsive to this invitation and created these pages for a book that ran the full spectrum of, you know, people who had died, people who had stayed home in another country or had moved away. And it felt very connective. But I didn’t, I didn’t want to say, this is so perfect, this is so connective. So I asked the kids, what was it like, what was it like to make this book? And these, this group was very sophisticated and very thoughtful and a whole bunch of the kids wanted to participate all the time. And said things like this felt really good. It felt like I wasn’t the only one who had a loss. This felt really special. It felt like it was okay to be sad. And they were saying things that reinforced my hunch and Leslie’s theory that inviting stories in that are hard can be helpful, can diminish isolation if you give them a place to live. And so this book was a place that the stories could live. We didn’t need to walk around talking about this loss all day long, but if we, if we wanted to check in with it, we could look at the book and kids didn’t have to be thinking and be distracted by this idea that they’d experienced loss because it had been acknowledged that loss is a part of human experience and that community sharing can can make you feel less alone with your loss. So this is a long-winded story and I think has a lot of other layers that I don’t know if there’s time in this podcast to go into. It’s one I’m still thinking about. I’m thinking about the questions that the children had about prejudice and about racism and about how this teacher and I encountered their questions and offered them answers, but we were both white women offering them these answers or these ways to think. And it’s made me think a lot about how much kids need a variety of voices, helping them understand the complexities of their own experience of the world, of this moment in the country too. From the emotionally responsive practice perspective, I felt that the teacher taking the risk to open a topic and to really invite reflection on this topic was an aha moment for her. And this group of children took the journey with her and they ended up making posters at the end of the book. And she did the entire book as a read aloud, leaving as much time for conversation as the kids wanted, which was a lot. And one of the things she was worried about was that she didn’t want the children to feel a complete sense of hopelessness about history and about racism. So we talked about the children being able to express both their understanding of racism and prejudice in this book and to be able to share if they had any experiences of racism and prejudice in their own lives. And then also to think about the word empowerment and to think about ways to find empowerment. This was also a theme that the book ended with. And so she had small groups of kids make this project where they depicted prejudice and racism in the book, prejudice and racism in our world, and ways that people find empowerment to work towards repair and change. And it was, it was very, very powerful. Then it’s hard to go away and not work with that teacher anymore and to think, where did she take this experience? What’s she going to do next? Where’s she going to grow? And that’s part of, I think, any ERP, we think about planting seeds for people and often not knowing when or where they’re going going to grow. And I think that what my coaching offered her at that time was partnership and thinking about something and thoughtfulness about how to care for children’s feelings while also having more of a macro picture of wanting to give them access to understanding about the forces of history, race and racism, and activism and collectivism, which all, which all stemmed from this book. Perfect.

Amy H-L: 00:35:33 Margaret, this seems to me to go to school culture and the idea that inviting children to bring their entire experiences, their life experiences into a classroom and feel safe about it does in a sense change the culture.

Margaret B: 00:35:57 It does. And in our different experiences with schools, depending on how many people in the school we work with and depending on whether we really work with the administrators, um, this kind of work can exist in the small bubble behind the closed doors of the classroom or can begin to have bigger effects on a school. I think some of the most important and most successful models we’ve had are when we’re able to have explicit time with administrators. And a lot of our work with grownups is giving them experiences. And I was thinking about this when I talked about Dewey and the importance of experience. We feel very deeply both in ERP and at Bank Street that in order to teach something, a grownup has to be able to have experienced something akin to it, to know what they want to try to provide, to try to create. And so we offer experiences for grownups to delve into their own memories and to try things like using a feelings chart to tell about how they’re feeling, using, uh, a journal to write about what’s happening for them that day. Before we get started on the content, I’m doing a go-around doing a check-in, a quick exercise about what color comes to your mind today, what’s .a landscape that you’re feeling like, and these beginnings are so important because the grownups connect to themselves first, then they connect to each other and then they’re able to listen to ideas that we might bring from a place of having experienced it themselves. We do have some aha moments for teachers in our seminars where we’ve heard things repeatedly. Like it felt so good to be able to just sit and write about what I was feeling. I’m going to make space for kids to do that in my classroom. And it’s pretty simple. It doesn’t mean that every teacher that comes in and has that experience goes back and the next day starts a routine. But I would say if we work with 30 teachers one day in a seminar, maybe two of them do go back and begin that particular practice right away. Maybe 10 of them carry the experience of having a space to talk about themselves and find another place to weave this in. Maybe 20 of them just sit with the experience of feeling valued and it’s not such a direct shift in practice, but as they come back to us over time, they are more open to thinking about different ways of interpreting kids because they’ve felt held and they’ve felt seen and known and respected and esteemed in a space that we made for them. I think I went down a long path and I can’t really remember where I began. You asked about school culture, right?

Amy H-L: 00:39:23 Thank you. That was very relevant to framework, the idea of inviting as in your words and inviting both teachers and students to bring their whole lives, their life experiences into the classroom.

Jon M: 00:39:46 Margaret, you started your, you began your teaching career in English-Spanish dual language schools. As you reflect on, on those experiences, what are your thoughts about dual language education? How do dual language classrooms differ from other classrooms and what are the ingredients of a successful dual language program?

Margaret B: 00:40:09 So I’ll start by just saying that even before I went into dual language, I worked in inclusion and I worked at IEPs [Individualized Education Plans], with identified special needs, into a setting that everyone was part of. Um, I brought that into my work as a dual language teacher and over time my, my understanding of the depth of the value of a dual language space has only increased. When I first began. I thought about things like what a, what a gift for children and what, what an asset for children to be bilingual, to be able to read, write and speak and communicate in more than one language. It’s a gift for children who are bringing a language other than English. It’s a gift for children who are learning a language other than English and it’s a space in which children can share their backgrounds with each other, learn from each other, and end up with this wonderful asset of being bilingual and of having more opportunities because of that. I still believe that all of those things are true. Emotionally responsive practice has helped me think about the emotional space of a dual language classroom. The vulnerability of being a second language learner and the idea that on any given day, half of the class, you know, ideally half of the class is operating in their second language and is, or in their new language, we don’t say second language anymore. We say new language because many children come with more than one home language and English is a new language, not a second language. So I think about the emotional safety of somebody in the room who does speak your language and your language being the operative language in the space, a feeling of home, home being valued in the space you’re in. And I think about the equity component that not only children who are native English speakers feel that connection and feel that value but children who are other language speakers feel that connection and feel that value. And then recently, and this is post my graduate work at Bank Street, Ofelia Garcia’s theory of translanguaging has become more and more widely recognized as an incredibly important way to view what children bring into the classroom. So when I was educated as a dual language instructor, we thought a lot about the English world and the Spanish world and the importance of getting children to operate in the language of the day and the separation of the languages. And it made a lot of sense at the time. It made a lot of sense in terms of not mixing up languages, of making sure that kids were completely fluent in both languages, that they weren’t what people said at the time was code switching as if it were a negative thing to do. And so if a child came in and said “hola” to me on an English day, I would say, hello, can you say hello? And I’d encourage them to, to say hello to me in English. And over the past, I’d say five or six years, coming back into Bank Street as faculty and having my colleagues working closely with Ofelia Garcia, who is one of main scholars who brought the idea of translanguaging into the, into our, into our thinking, um, I’ve really transitioned my way of understanding the English space, the Spanish space, and the idea that while a dual language classroom does provide both languages with clarity, that what the children bring in needs to be valued in whatever language or mix of languages that it comes out in because children use all of their language resources to, uh, to let you know what they know and to learn. We’ve had some wonderful professional development at Bank Street. Recently at the language series we had a keynote who spoke very practically and gave us this wonderful example where we needed to decode something that was completely unfamiliar. And she said, and we had to work with a partner. And she said, how many of you spoke to your partner in a different language? How many of you spoke to your partner in English? We all spoke in English as we tried to decode something unfamiliar. and in a classroom where you said, you’ve got to operate in Spanish today, those children wouldn’t be able to use their cognitive resources if they weren’t fully fluent in Spanish yet. So there’s many, many important examples of where translanguaging fits into a classroom, but I think it’s, it’s really important that anybody coming into a dual language setting learns about studies and tries to bring into their, their worldview this idea that, um, if a child goes back and forth between two languages as they speak, it’s not the moment for the teacher to correct them. It’s a moment for the teacher to embrace the knowledge that they bring and embrace the stories that they bring with, of course, the ultimate goal being children becoming fully fluent in both languages, becoming fully literate in both languages, that the pathway to that fluency is not by restricting their, their output or their input. Mmm. Along the way.

Jon M: 00:46:59 Could you, I think you’ve been describing it in practice, but could you translanguaging for people who aren’t familiar with the term?

Margaret B: 00:47:07 I’m not, I’m afraid I’m not going to do it justice because I was, I didn’t prepare myself to say this ahead of time, so I’ll give you my operative definition, which is that children who are learning more than one language as they learn and grow in school, bring all of their language resources into play as they learn and make relationships and have experiences. This often entails going back and forth between two languages, substituting a known word from the other language within a full sentence in the other language in order to express yourself. Um, translanguaging means that language is one thing that we do. There isn’t a Spanish section of my brain and an English section of my brain, although we thought there was. There’s a language center in which both of those things, um, when I’m using English, all of that language center is operating when I’m using Spanish, all of that language center is operating. So translanguaging is the idea that on the route to fluency there is a need to go in between the languages that, you know,.

Jon M: 00:48:33 Thanks.

Amy H-L: 00:48:33 Margaret, you’ve been a kindergarten teacher and you’ve taught many kindergarten teachers. What’s the most important advice that you would give a beginning kindergarten teacher?

New Speaker: 00:48:45 Ah, well there’s so many different pieces of advice. I am going to share that when I was a kindergarten teacher, every single year I would read a chapter in this book, which this was long before I worked for Leslie Koplow’s program. It’s called “Creating Schools That Heal: Real Life Solutions.” And chapter three is called Saving Kindergarten. And this is a chapter that talks about the development that happens during kindergarten. And I think one of my biggest pieces of advice is learn about child development and kindergarten. Consider the fact that some of the children coming into your kindergarten, if you’re a public school teacher, will be four and a half while others are five and a half. And remember that four and a half and five and a half or developmentally very different places and then meet them where they are. Part of that, meeting them where they are is inviting their families in. And this is something that I practiced over my years, which was an intake interview in which I considered the parent, the expert in which I had nothing to tell the parent about their child yet, that it was all what they could tell me. And I think that this is an essential tool of a kindergarten teacher and really it’s a wonderful practice I think at any grade level, but particularly as children enter into school, into formal school for the first time. And many kindergartens are so academically oriented that it really feels like school, that knowing what they, their parents, know about them and uh, offering partnership to parents is an essential piece of the success you’re going to have with any given child. And I think the third piece of advice along the lines of development, and this is really something that Leslie articulates beautifully in the chapter I mentioned, is that on the road to what we call independence, there needs to be a dependent partner. There needs to be a grownup who is what Leslie Koplow calls your psychological home base. You as a grownup need to make yourself a safe grownup, someone who the children can turn to in need, someone who’s going to honor them even when they’re doing things that surprise you, like running around the room or throwing things on the floor or pushing other kids. That, knowing that being able to come back and depend on you is how they’re going to get more and more independent over the years. And this is a place where I think it’s a nice example of how emotionally responsive practice brings in early development. And we often remind people about toddlers and how toddlers will as they learn to walk and crawl, will go off from their grownup and explore something and then all of a sudden get a sort of feeling and look back and need to scurry back or run back to their grownup for a hug or for a connect or to show them something and they do this dance of go away and come back, go and come back. And that this is something that if kindergarten teachers can understand, they can offer to kids in the different ways that particular kids need it. Um, so when kindergarten teachers demand full independence in October, it’s really not, it’s not going to work for some kids. But when they have an idea that kids are going to gain independence over the year through feeling like they can depend on their teacher, then it really is going to work. And that those kids are going to feel prepared emotionally to step into the world of school as they become first graders. And then go back to the concept of inviting and containing and make sure your classroom has a routine that’s dependable. Make sure you’re always reading kids the schedule. If I have a magic wand, I would wish that every kindergarten teacher, never preschool teacher and really every teacher, because I did this with my grownups too, would read through the schedule every day and if there were going to be any changes, they would talk about it. And as one activity ended and another began, they’d look back at that schedule, that visual, that place that holds the expected, that holds the, what you can depend on in place. And that teachers would never say to me, “Oh, they know the schedule by now. So I don’t read it anymore to save time.” Um, I would say read the schedule every single day. You won’t regret it.

Jon M: 00:54:09 Is there anything else you’d like to add that we haven’t talked about?

Margaret B: 00:54:11 I think there’s probably hundreds of things I’d like to add and I’m looking back at the notes I wrote before we spoke and I don’t, I don’t think there’s anything, anything that was really burning in my mind that I needed to say that I didn’t say. Uh, well I think there is one, there was a question that I don’t think you asked, which was about the connection between special education and bilingual and dual language education.

Jon M: 00:54:46 So please, yes.

Margaret B: 00:54:48 Yeah. And that’s something that I have thought about a lot and it plays into what I talked about during the section where I was talking about dual language and translanguaging. And because I came from a an inclusion setting, I had a lot of techniques that I used to make language comprehensible and to invite children to join in using the language that they had even though the inclusion setting that I worked in was all was an English classroom. And so because the children worked with speech therapists and occupational therapists and physical therapists, we would often incorporate some of the things that they did in their sessions with their therapists into our classroom practice. So for example, if therapists were using American sign language as a bridge to oral language, uh, we would use that in the classroom, too. So all the children recognized and used simple terms like stand up, sit down, more family, I won, thank you, bathroom, water. And when I came to dual language, I thought this is an important component of dual language too. If I say the word bathroom today and teach the children the sign and I say the word “banyon” tomorrow and show the children the same sign and then I continue that sign over the days, the children who are in their new language that day will have a much higher chance of comprehending what I’m talking about because they’ve got this visual, this gesture clue. So the use of the schedule, the use of the visuals, the use of real objects as you talk, the idea of making your language comprehensible. And it’s funny to be talking about this on a podcast where nobody can see me and they can’t see if I’m moving my hands or if I’m pointing to anything. And it’s a very, it’s a very language based form of learning and form of taking in. And you know, I, I wouldn’t use a podcast to educate kindergarten children in dual language or in inclusion settings or even a non inclusion and non dual language settings because we understand a lot better when we have multiple sources of input for the content that’s being shared and when we have multiple ways to express ourselves. So I’d really like to invite teachers to consider, um, whether you’re in a dual language inclusion special education or, or a general ed monolingual classroom, consider adding even more visuals, gestures, sign language and actual objects into the way that you present information in language and consider allowing children to use those options as well as they let you know what they know even when their language is not yet caught up with their knowledge. And I think the other, I think the note I’d like to end on, we were talking about this in our emotionally responsive practice staff meeting just yesterday, in fact. And one thing we are really grappling with as more and more information comes our way about how to decentralize the white experience as the first or the only experience. We’re talking about this a lot because at this point in time the six staff members that are at ERP are all white women. And while this has not always been the case, and I hope will not always be the case, due to a lot of different circumstances and a lot of components, it is the case right now. So we’ve been intentionally opening a space to reflect on this as we think about the different schools we work with, different teachers we work with and we’ve been thinking about how do we make sure that what we’re bringing in as emotionally responsive practice, uh, feels connective, feels right, feels like it, it works within any school culture, within any teacher’s personal culture, within any group of kids’ culture. And there is not an easy answer to this. I think, um, maybe we could talk more about it with you in a year or two as we embark on really intentionally thinking, think about this question. But what did come up is what do we, what do we really believe universally? And one of those things that my colleague no well articulated was that human beings, there are some universals that we believe about the human experience that human beings make attachments and that those attachments nurture our development, that human beings need comfort. And that comfort might come in a lot of different forms and that human beings thrive when they are seen, when they’re validated, when they’re heard, when they’re understood, when they’re known, when they’re valued. And I wanted to say that it’s a journey for all of us to consider whether we are authentically doing this with every grownup we work with as we ask them to do this with all the children they work with. And I’m very excited to be able to collaborate and think together with [inaudible] really thoughtful, reflective people both in ERP and in the larger educational world. But it is a a long journey that we have to take together and it feels like a real honor to be able to come into spaces of teachers and spaces of families and spaces of children and offer them something and also adjust my offering to be what is right for them, what’s relevant to them. And I look forward to continuing this journey with intention..

Amy H-L: 01:01:35 Thank you so much, Margaret.

Jon M: 01:01:38 And thank you listeners for joining us. We’d like to hear how you’ve incorporated ideas you’ve heard on our podcast or read on the blog. Please email us at posts at hosts@ethicalschools.org. Check out prior episodes and articles on our site and we’ll also host some of the things that MArgaret was talking about today. We also offer professional development for schools and youth programs in the New York city area. Contact us for details. Again, it’s hosts@ethicalschools.org. We’re on Facebook and Twitter @ethicalschools, and Instagram. Our editor and social media manager is Amanda Denti. Till next week.